Horror has always been linked to challenging societal norms, applying commentary on the unknown, whether its topics around gender, race, sexuality and any other of society’s taboos. Unlike any other film genre, the genre is linked to the fear of the unknown, the return of the repressed, whether that’s the return of a zombie from the grave or confronting societies repressed notions of sexuality. 1985’s Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge has been analysed as metaphorically focused on gay repression, 2000’s Ginger Snaps uses the werewolf transformation as a metaphor for puberty, and 2008’s mockumentary feature Lake Mungo uses its ghost story as an exploration around grief. These are all prime examples of horror being metaphor, but no director can summarise this more through his work, then George A. Romero and his Living Dead franchise. Made up of five central features, the films would be a staple in the zombie sub-genre, creating the commonly accepted version of the monster for modern audiences. His initial feature, 1968’s Night of the Living Dead, became a metaphor for racism in complete accident, recontextualised in its time and through its central casting, when Romero had no plans to make the film metaphorically about anything at all.

The positive reaction to this aspect of his debut feature led to the original Trilogy of the Dead being heavily focused around political and social commentary, 1978’s Dawn of the Dead and 1985’s Day of the Dead being clearer with its commentary, built into the narrative rather than being analysed retrospectively. Twenty years later, the franchise would continue with 2005’s Land of the Dead, the film continuing the franchise’s lack of continuity, joined together by the similar exploration into a group of survivors trying to thrive in a zombie infested America. Land of the Dead updates the franchise to the modern day, making the use of phones, and reflected Romero’s future with the franchise, following with 2007’s Diary of the Dead and 2009’s Survival of the Dead, which would both tackle modern commentary through the lens of the zombie feature. Survival of the Dead would be the final feature of the late director, dying in 2017 at the age of 77, during pre-production on his newest feature in the franchise, but the director left behind a compelling legacy of social commentary in the zombie feature.

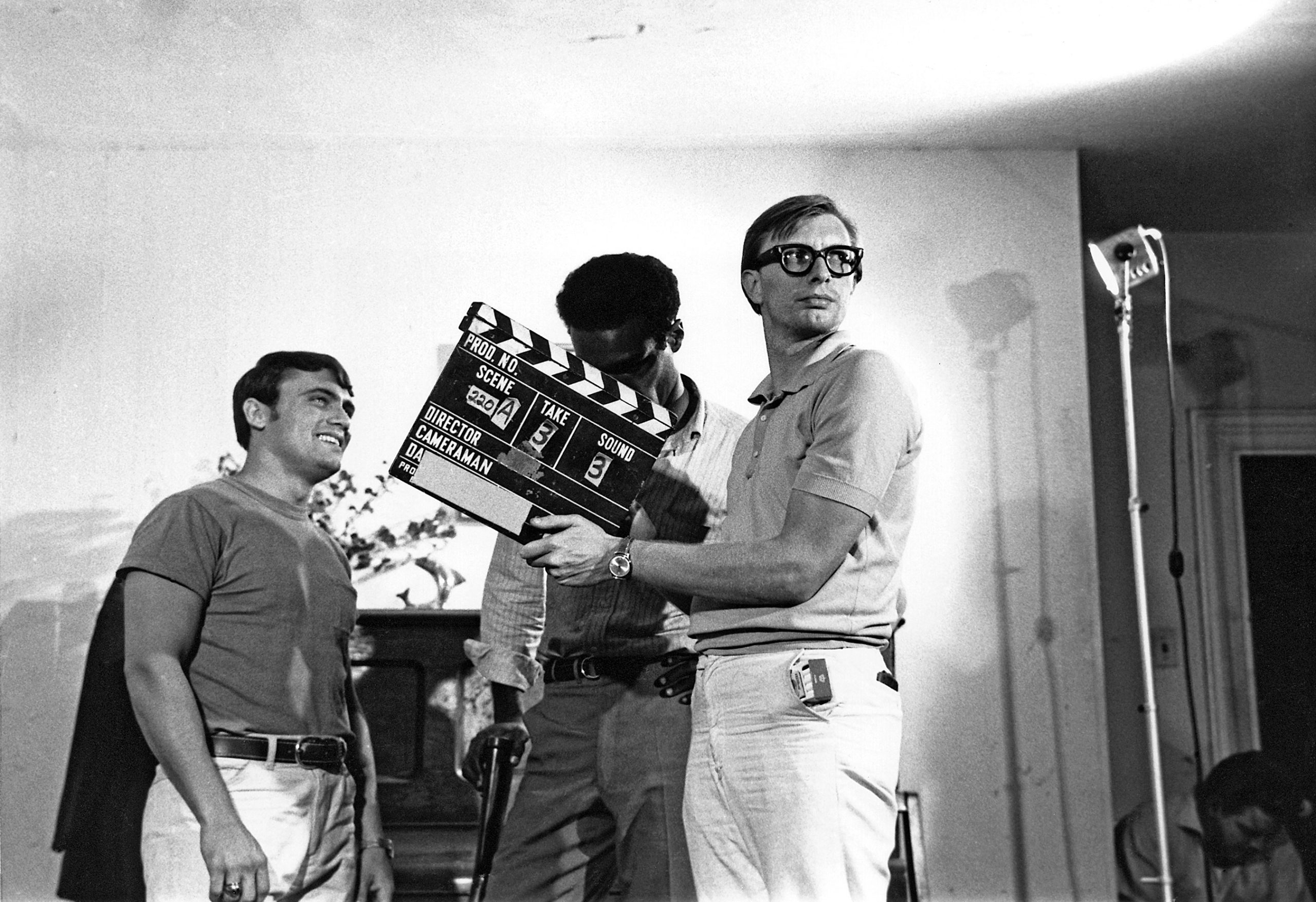

The zombie feature found prominence with the release of the 1932 feature, White Zombie, with the original concept of the zombie focusing on African voodoos, capitalising on a race angle as African characters being villains, turning white characters into mind-controlled puppets. It was rooted in America’s obsession with African mysticism, and that concept of the zombie would not change until Night of the Living Dead. Made on a miniscule budget and shot in black and white to save costs, the film never actually refers to the flesh-eaters as zombies, rather as ‘ghouls. The film set up the precedent of the creatures rising from the grave, their craving for brans, infecting others and the slow-walking nature of their movement, with the film’s implied backstory for the infection coming from radiation from a fallen satellite. The casting of African American actor Duane Jones, who had been cast by Romero because he was the best actor for the best part and not because of any racial undertones for the plot, moved the narrative into one being composed of a racial angle. Prominent black characters in mainstream Hollywood were increasingly uncommon, so the first major black protagonist in a horror feature being gunned down alongside the monsters of the film by a horde of white men seems to have major political meaning. Critics have long compared the death of Jones’ Ben to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr and compared the ending to the multiple African American causalities of the civil rights movement.

Ben is shot down in the movies’ conclusion, as the white hunters mop up the remaining zombies left after morning rises, and confuse him as a zombie. Ben represents a racial other, joined forth with the zombies as a racial threat, a victim of white America. His presence in the film comes as a threat to the white suburban home, as he finds solace in what he believes is an abandoned home, only to come face to face with a father, child and mother. The conflict of the movie comes from the butting heads between Ben and the father, as Ben takes the upper hand and the father’s insistence to not listen costs his family their lives. The white family feels threatened by a black man in their home, the film aligning him more with the zombies outside, the family seeing him as mindless threat just like the undead. Even without meaning to, the film draws incredibly clear racial messaging, confronting headlong into the black experience during the civil rights movement.

The credits roll in 1978’s Dawn of the Dead by showing the zombies walking around aimlessly the mall that the central characters of the film once called sanctuary, multiple still shots showing the zombies acting as mindless as the shoppers that once roamed those very aisles. Dawn of the Dead very much tackles the concept of consumerism head on; it’s a film where Romero realised, he could imbue his movies with specific actual messaging that would not be forced onto the film after release. In the present day, shopping malls are very uncommon, in a world where most shopping can be done on your phone, but during the time of release, shopping malls were a societal norm which represented the capital of capitalist spending. Most of the runtime of the film takes place in the very shopping malls that represent America’s interest in consumerism, as the characters find solace and happiness in meaningless items, walking around in new clothes and taking part in various montages as they move from shop to shop. The items mean nothing in an apocalypse, and once the zombies descend into the building, stacked outside like an army of shoppers waiting for the doors to open, the items become just part of their fight for survival, no different to how they were trying to survive beforehand.

Shot in colour and with a larger budget than his previous feature, Romero uses the movement in the zombie genre since the release of his previous feature to highlight the impressive zombie makeup featured here. The zombies all wear distinct outfits, matching the professions that they had when they were alive, less a horde of similar monsters and more now a group of victims that resemble the humans that kill them. Even zombie children are included, who our protagonists have a moment of hesitation for, wondering if they will kill a child. The outfits make them blend into the shopping districts, they are one in the same as the groups that have used this as their home, as brainless as the people who make shopping and commercial goods part of their need to survive. The protagonists can escape, using a helicopter on the roof, but the zombies are not so lucky, stuck wandering the halls of a dead mall, a mall which has no monetary value in a world which does not run on money and spending. The zombies are victims in Romero’s mind, forced to repeat their meaningless monetary existence in both their life and death.

Dawn of the Dead’s opening sees a group of media agents trying to downplay the current zombie crisis, showcasing the media hiding the truth from the public as a breakdown in information and communication leads to it all going array. Breakdowns in communication and distrust of governmental bodies makes up a major focus of Day of the Dead’s narrative thrust. The film is contained to a small underground bunker in Florida, where a group of survivors, made up of scientists and military personnel must decide how to continue society after the zombie virus has got even worse. Romero mentioned in an interview after the release of Dawn of the Dead, that he saw the zombies as sympathetic characters, as the real victims of the entire conflict, and that’s how this movie depicts the characters. In the final decade of the Cold War, the movie released during Ronald Reagan’s presidency, a period where the president led America to becoming more consumerist but also helped private owned businesses and struggled to respond to the threat of AIDS. It was a period which was uncertain for the American citizen, and Romero’s feature reflects that, showcasing the worst of the military personnel and the scientists that should be trying to stop this zombie threat. Zombie media frequently boils down to narratives which reveal that humanity is the real villain, even with all the zombies featured, it is the basis of every season of The Walking Dead series, and Romero seems to be where this factor began. The characters bicker at each other, turn on each other constantly and the scientists are taking part in inhuman tests on zombies, so bad that the lead scientist is nicknamed ‘Frankenstein’.

With zombies becoming more part of their regular everyday life, the zombies have moved from horrific to a part of life that the military personnel enjoy, loving the sport of dispatching the zombies one by one. They are sexist to the female lead, violent and Joseph Pilato’s performance as Henry Rhodes leads him feeling more mentally insane than trustworthy military man. A film needs a protagonist then, and the only way the film can keep up with this need is making the zombies the protagonists, and specifically a domesticated zombie, known as Bub. In a world where humanity has been taken over by flesh-eating zombies, the only actual human thing in the bunker is one of the zombies, as the deaths of the various military personnel becomes cathartic to the audience. The zombies are contained to their nature, they cant help being monstrous, while the humans decide to be cruel, it instinctively reflects the feelings of unease and distrust in America, when the monster is the hero, how does that reflect on who is meant to be the good guys.

Sympathy for the zombies becomes the backbone of Romero’s return to the zombie genre, in Land of the Dead. The zombie sub-genre was back, popular at the box office once again, after the success of 28 Days Later and Shaun of the Dead, and these successes allowed Romero the chance to make another zombie feature. Land of the Dead builds on various aspects of Day of the Dead and contains elements that were scrapped from that film because of budget restraints. Years removed from the initial zombie outbreak, humanity survives in city-states across North America, where the rich live in high rises and in safety, and the poor live in the outskirts of the guarded cities, forced to survive in squalor. Consumerist goods become a means to an end in this new society, used by the paramilitary personnel to barter for money, housing and favours with the leader of the city, Paul Kaufman. The poor are given worse goods when the paramilitary travel for supplies, giving the rich goods to the upper classes and the spoiled foods to the poor. The features’ plot gets into focus when one of the army men takes Kaufman’s rich army vehicle, bartering it to get the apartment that was promised to him, each character is just fighting to survive in a world where consumerism is used to subjugate them and keep them in check.

The zombies featured, led by a former gas worker, known as Big Daddy, fall in line with the poor of the city. Zombies are used as threats in the town, forcing prostitutes into cages with zombies for entertainment, its Romero continuing his view of the rich and governmental bodies being unfair and the true evil. The zombies gain sentience, as Big Daddy can learn how to use a gun, and is able to have enough mental capabilities to become a leader to the zombie horde. By the end of the film, the zombies and the paramilitary both storm the city, both using guns and taking down the rich. When it comes to face off, the zombies spare the humans and walk away, recognising each other as societies just trying to survive. The movie’s exploration into the split between the rich and poor is very clear, and reflects a movement in Romero’s film-work, where his metaphorical messaging has become less like metaphors, and is clearer and more heavy-handed. It is a continuation of the themes that appear in the previous two features, but with a modern and less polished look.

Romero’s final works for the franchise are easily his worst, and less fleshed out compared to the previous four. Diary of the Dead takes place during the initial outbreak, shot as a found footage film with Romero seeing out of his depth in exploring the zombie as a metaphor for modern media. It is a thinly veiled look at the disinterest in violence in the modern day of cameras and social media, and the commercialisation that comes from that new world, but it’s just a worse version of Romero’s previous exploration of those themes. Romero stated in an interview after the release of Zack Snyder’s remake of Dawn of the Dead in 2005, that the exploration into consumerism would not work in the modern day, and that was proven right by his own feature. Survival of the Dead works more as a zombie feature because of its lack of major metaphorical themes, outside of the continued narrative thread of the distrust of the military, it’s a narrative sure zombie feature. They both continue the zombie as metaphor staple of Romero, a factor that unites his Living Dead franchise, a franchise that is without any actual continuity. Zombies are seen as victims, representing themselves as both villain and protagonist, and reflecting the messaging fitting the period, from racism, to consumerism, to distrusting governmental bodies, and finally, as a mirror of the feudal system.