John Carpenter is one of the masters of the horror genre, forming the basis for the slasher sub-genre, but also dabbling in the psychological horror, the science-fiction horror and even wandering outside of the horror genre. He is characterised heavily by pessimistic and nihilistic films, and by composing his own scores for his features, becoming a soundtrack artist long after he has finished being a filmmaker in the modern day. With the upcoming Halloween season, following will be a ranking of the eighteen theatrically released films directed by the horror auteur, not including his direct to television features or his involvement in anthology features.

18) Ghosts of Mars

Starting the list off, comes Carpenter’s second most recent film released into cinemas, 2001’s Ghosts of Mars. Starring a central cast of Natasha Henstridge, Ice Cube, Jason Statham and Pam Grier, the film centres itself around a future where Mars has been colonized. A squadron of police officers and a convicted criminal are forced to work together to fight against the possessed residents of a mining colony, with the ghosts of the planet’s original inhabitants taking control over the peaceful residents. The film has slowly become a cult classic to many fans of the director’s work, but the film also marks a downward trend in the director’s late career, from the 1990s to the present day. The film essentially serves as a remake of one of Carpenter’s classic features, Assault on Precinct 13. Just like that film, the feature brings police officers and criminals together to stop a gang that essentially act as zombies, mindless monsters that exist as cannon fodder in various action sequences where they try to break into one building.

Where that original feature is entertaining, this film just blends itself in mediocrity, with all the central players failing at making their characters feel convincing or entertaining. The film lacks the central feel of a Carpenter feature; his nihilistic characters and plot lines are replaced with a film that feels more campy and embarrassingly unfunny compared to a genuine horror-action feature. Carpenter’s score feels generic and unimpressive, lacking a unique hook that makes it stand apart, and the direction flounders in keeping up with the set style of 2000s horror, with an oversaturated look and shaky camera use that makes it fall in line with the eventual style that Saw, in 2004, would set for the genre. Action sequences can be fun at parts, but when the film stands out so much from the general quality of Carpenter’s work, it is hard to praise anything in the feature

17) Village of the Damned

In a 2011 interview, John Carpenter described his remake of Village of the Damned as a ‘contractual assignment’ that he was ‘really not passionate about’. Starring Christopher Reeve, Kirstie Alley, Linda Kozlowski and Mark Hamill, the film follows what happens after all women in a town are impregnated by brood parasitic aliens, with the children growing rapidly and having psychic abilities. Based on 1957’s The Midwich Cuckoos, the book has created various adaptations of the work, with 1960’s Village of the Damned and its sequel, 1964’s Children of the Damned, being the basis of Carpenter’s remake. The novel also spawned a television remake, sharing the same name as the novel rather than the film version, released in 2022. A remake of Village of the Damned had been in the works for a decade since the popularity of 1978’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, with the adaptation being aimed to tackle the subjects that the original film could never tackle.

With censorship at the time of production, the original could not even mention impregnation and could not explore the true focus of the narrative, abortion. Outside of this big change with the lack of censorship, Carpenter’s version of the narrative just falls short and ends up feeling campier than a serious outlook on abortion. Reeve’s final role before he was paralysed in 1995, both him and Hamill feel miscast in their roles and fail to convince as serious stars, and the score suffers, similarly to Ghosts of Mars, as feeling generic, and at times, out of place in such a dramatic feature. The film marks the ‘work for hire’ time in Carpenter’s career, with the 1990s serving him badly with a lack of creator-owned projects.

16) Escape from LA

A fifteen-year late sequel to Carpenter’s classic feature, Escape from New York, 1996’s Escape from L.A, is a derivative film that feels in line with sequels to 80s classics. Similar in case to features like Ghostbusters 2, the film serves more as a remake of the original film than a direct sequel, with very little callbacks to the original and more of Carpenter just doing the same plot beats again. Set in a near-future world of 2013, where the United States is ruled by a President for life, the film sees Snake Plissken returning into action when the president’s daughter steals the remote of a new superweapon. She finds herself in L.A., which has been walled off from the rest of the States as a prison-city, and Plissken is tasked to save her and retrieve the weapon to stop his upcoming deportation. Carpenter has long declared his sequel to be his favourite of the two, stating his reasons as because of the film’s darker and more nihilistic tone and its deeper themes, but the film fails at being either of these things.

A competent film, but a lesser feature when compared to Carpenter’s original, the film feels sillier and more cartoonish than a darker feature. Scenes including a paragliding action sequence, a chase on surfboard and a showdown between heroes and villains through a basketball game come across as goofier than anything, and the turn from impressive miniatures and practical effects to poorly aged digital effects lead the film looking less impressive than ever. Originally, the film would be followed with an end of a promised trilogy, as Escape from Earth would double down on the special effects, however the poor box office performance left all plans for the franchise on the cutting room floor. The shining light of the film comes from Kurt Russell’s still impressive performance as Plissken, he is still committed to making the character cool and the character never flounders when the rest of the film does.

15) The Ward

There would be a nine-year gap between Ghosts of Mars and Carpenter’s most recent big screen venture, 2010’s The Ward. He has since directed an episode of the streaming series Suburban Screams in 2023, but until then this was his most recent directorial work, with the director falling out of love with the medium in the years since Ghosts of Mars. It was during his short stint working on two episodes for Showtime’s anthology series, Masters of Horror, that his love for the medium returned. The Ward sees that love for return, and though it is nowhere near groundbreaking, it is a chilling story that proves that Carpenter still can make a tension inducing and briefly scary feature. The film follows a young woman who is institutionalized after setting fire to a house, and once arriving at the institute, she becomes haunted by the ghost of a former inmate at the ward. Starring Amber Heard, Mamie Gummer, Danielle Panabaker and Jared Harris, the film suffers from a script that undermines everything Carpenter has done with the atmosphere and setting.

Characterisation is basically null in the film, with each inmate having one personality trait, and the late-game reveal that the narrative is all happening in one person’s head, and no one is real gives that a reason, but leaves the film feeling cheap and empty. Knowing the central twist as well, leads to the film feeling impossible to enjoy on a rewatch, when nothing that is happening on screen is real, it is hard to become invested.

14) Memoirs of an Invisible Man

The production of Carpenter’s take on H.F. Saint’s novel, Memoirs of an Invisible Man, would be hellish and would almost make the director want to quit, a hard start to his downward trend in filmmaking during the 90s. The film was backed by the studio because of Chevy Chase’s intense interest in using it as a star vehicle to move him from being a comedic actor to a serious star. The star was most well-known off the back of his stint on comedy series, Saturday Night Live, where he starred from 1975 to 1976, and then a comedy leading man in films like 1980’s Caddyshack and the five National Lampoon’s Vacation movies. His move to serious actor was a confusing one, and the departure of director Ivan Reitman, famous for Ghostbusters, came about because of these budding heads of tone, with Carpenter eventually hired after Superman-director Richard Donner left the project after eight months.

The film follows Chase as Nick Halloway, a man who is rendered invisible after an accident, and he soon becomes the target of a CIA operative who sees him as a potential new weapon for the American government. Chase wanted to base the film in drama, focusing on the troubles a man would have when becoming invisible and how that would drive him away from his friends and family, and wanted the film to be a central love story. This is where the film falls flat, Carpenter directing a light-hearted comedy drama, where the main star is refusing to do the comedy aspect only leads to disaster. The film is tonally confused, and there are interesting uses of the invisibility effects, and a fun performance by Sam Neill, but Chase only bewilders in his performance, and the central connection between him and love interest Daryl Hannah is nowhere to be seen. The troubled production has only led to an equally troubled feature.

13) Vampires

When asked in an interview on his opinion of the filmic version of his novel, Vampires, author John Steakley pointed out how the adaptation retained much of his dialogue but none of his original plot, though he liked the film. Carpenter’s 1998 film Vampires has become a cult classic since its release, spawning a franchise which contains two direct-to-DVD features, 2002’s Vampires: Los Muertos and 2005’s Vampire: The Turning. Moving away from the gothic loneliness that the monsters were known for, Carpenter’s film tackles the vampires as bloodthirsty monsters which more resemble zombies than anything like the Draculas of the past. Starring James Woods as Jack Crow, who leads a team of vampire hunters, after being raised by the Catholic Church to become their master vampire slayer. The plot kicks into gear after his crew are killed, and he must pull together new members to take down the first vampire, Jan Valek, who is after a centuries-old cross. The plot is paper-thin, essentially a series of engaging action sequences that are stitched together by something resembling a plot.

The film has become a cult classic because of its reliance on action, it is a movie trying its best to be cool and kick-ass, with a central performance by James Woods that feels laughably over-the-top at times. Carpenter has always wanted to make a Western, with many of his films falling into Western-lite at times, with Ghosts of Mars and They Live being the prime examples. Vampires serve as the closest to a Western for Carpenter and showcases his tendency to make his films increasingly goofy and comedic in the 90s, but its also hard to be completely invested when Carpenter makes all his characters so increasingly unlikeable. It has gained a cult-following in the years since but outside of some great action and some maybe not on purpose-comedic moments, it is hard to see why.

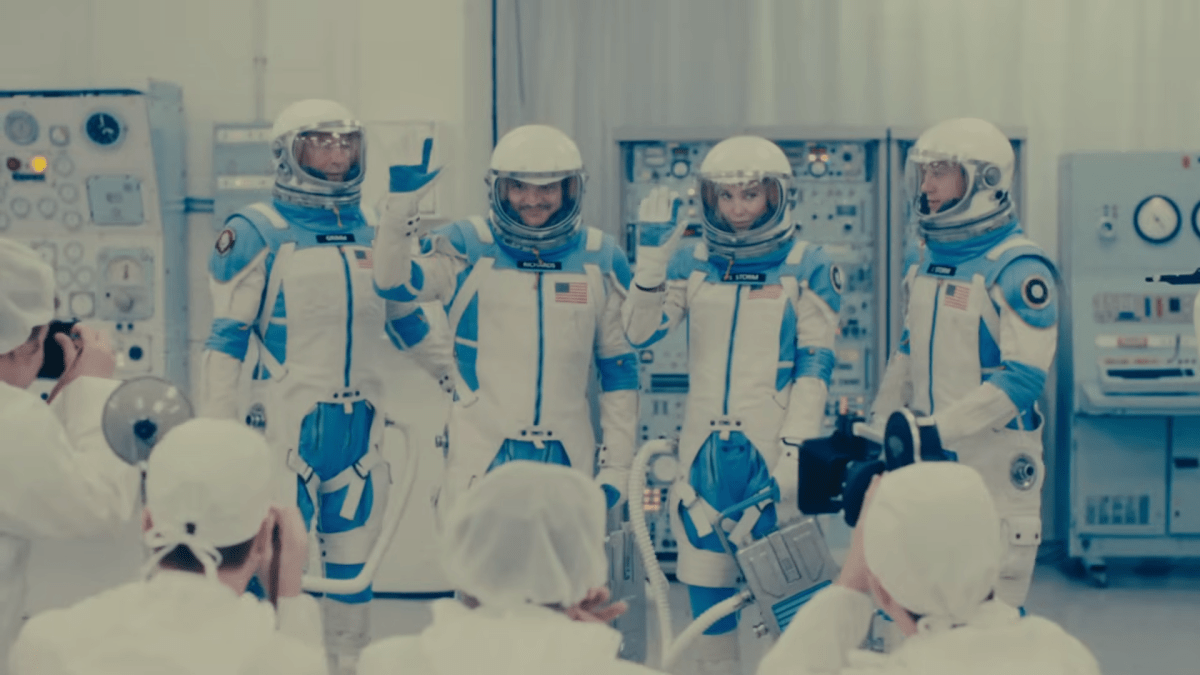

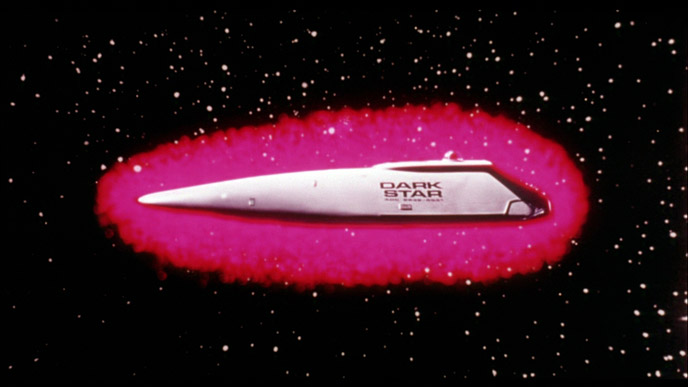

12) Dark Star

Serving as Carpenter’s debut feature, the science-fiction comedy, Dark Star, is a bit rough around the edges as a student film but has enough charm and is important enough to the genre that it deserves to be high enough on the list. Set up essentially as a spoof of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the film went through a journey from University of Southern California student film, to expanding with reshoots in 1973 and then having a limited theatrical release in 1975. Serving as Carpenter’s first directorial project, the film also offered Carpenter his first chance to score a feature. The film follows the crew of the deteriorating starship, named after the title of the film, twenty years into their mission to destroy unstable planets which might threaten the future of galactic colonization.

The film feels messy at times because of the clear inclusion of various random sequences to lengthen the runtime of the film, with the film’s plot essentially being a bunch of comedic sequences one after another until the central bomb plot takes place in the back half. The film does not really get going into that secondary half, but the inclusion of a beach ball alien is humorous and makes up for some of the shortcomings of the set up. Outside of making a career for horror auteur John Carpenter, the film is equally important for launching the career of Dan O’Bannon, who would take the beachball alien concept and turn it into screenplay of the hit 1979 film Alien. His animation work here would also lead him to provide the special effects animation for 1977’s Star Wars, setting himself up as a signature creator for the science-fiction genre, and marking the importance of Dark Star as a figurehead of the genre.

11) Christine

The opening sequence of John Carpenter’s Christine sets itself apart from the original novel instantly, as the film opens with the creation of the signature car, with the car instantly revealed to have a mind of its own as it injures a mechanic. The film marks a connection between Christine and femineity, the car strikes out in anger when a man touches herself in a private area, and later becomes jealous when Arnie, it’s owner, becomes entwined with another woman. It is far away from Stephen King’s original concept for the central car, where the car was possessed by its previous owner, marking it as a normal car made evil through possession, where Carpenter’s is evil from the assembly line. Like Kubrick’s take on The Shining, this had led King to disliking this version of his novel, but outside of this central origin difference, and some more cinematic depictions of the death sequences, the film is faithful to the textual events. The film was handled by Carpenter as a work-for-hire job, while he was trying to develop a filmic version of King’s other novel, Firestarter. The film follows Arnie Cunnigham, as his life takes a dramatic change when he purchases the car known as Christine, which only becomes worse when he meets a new girl at school, and the car begins to take control over him.

As a work-for-hire job, the film excels in showing the class of Carpenter’s 80s work, working hard to make a car scary and capable of gruesome kills. The film conveys an interesting personality through an inanimate object, and Keith Gordon’s central performance as Arnie holds the film together perfectly. The character is as multilayered as the novel, the film spending so much time away from the character so that by the end of the feature, he feels as evil and alien as the car, Gordon tracking a change in his performance, from innocent and kind student to a crazed murderer. Even if King does not like this version of his work, it has the spirit contained in it for sure.

10) Prince of Darkness

The second instalment in what Carpenter names as his ‘Apocalypse trilogy’, alongside The Thing and In The Mouth for Madness, Prince of Darkness is a mix between Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead and Evil Dead 2. Starring Donald Pleasence, in a welcome return to the world of Carpenter after last being in Halloween, and a larger cast, the film follows a group of quantum physics students who are assigned to assist a Catholic priest. The priest has found a liquid at a local monastery, which they soon come to find is a sentient, liquid embodiment of Satan himself. At heart, the movie is a possession film, a possession takes on The Thing, as the characters fall one by one to the possession in a similar way to that previously mentioned feature. Like Raimi’s Evil Dead movies, the charm comes in the possessed creature effects, and the compelling ways that each character plays their possessed self-compared to the original character, mixing the serious nature of Evil Dead with enough goofy and comedic performances that makes it stand toe-to-toe with Evil Dead 2. The central romance of the film feels underwritten, but each other aspect of the film more than makes up for it. An early found footage scene is included, well before the concept boomed with the release of The Blair Witch Project, and the film works to convey a film brimming with doom and despair.

The liquid possession angles the film explores seems to be a clear comparison to the AIDS epidemic that was still raging during the release of the film. The possession is transmutable, passing via fluid transferred between person to person. Similarly, the film also transmutes many references to homosexuality across its runtime, namely through a sequence where Walter, an implied gay man, is only able to escape from a group of possessed women, by coming out of a closet. Homosexuality, at the time, was believed to be the only sexuality to be infected by AIDS, marking a deeper meaning in a tonally comedic film, balancing both comedy and heavier themes perfectly.

9) Assault on Precinct 13

Carpenter’s second feature as a director is essentially a remake of George A. Romero’s classic 1968 feature, Night of the Living Dead, only swap out the mindless undead instead for an army of mindless gangsters. The film even retains Romero’s accidental social commentary by focusing the film on a black lead during a time where that was a phenomenon in mainstream cinema. Originally developed as a straightforward Western, a film that Carpenter has always wanted to create, the film explored a similar plot to Rio Bravo, where a sheriff’s office is attacked by the local rancher’s gang when the sheriff arrests the corrupt rancher. When the film lacked the budget required, the film was downsized to taking place in the present day instead, following a police officer who must band together with a death row-bound convict to defend a defunct precinct against a criminal gang. The film opened to mixed reviews, and a dwindling box office performance, but would soon become a cult classic, allowing it to even garner a remake in 2005, starring Laurence Fishburne and Ethan Hawke.

Even if no longer a Western, the film still retains Western components and features a running gag of the line ‘Got a smoke?’, a reference to the various cigarette gags that came from Howard Hawks classical Westerns. The film features a poppy score from Carpenter, a synthy electric score that breaths strong life into the action, as the station gets swarmed by army after army of faceless goons. The film’s most shocking moment, however, comes from the execution of a little girl in bloody fashion, an event that kicks off the central plot of the film after a slow start of plot build-up. The MPAA threatened that the film would receive a X rating if the scene was not cut from the film, and Carpenter relented, removing the scene from the copy he gave to the MPAA, but distributing the film with the scene still present to play coy with them. It was for the best that the film retained this harrowing sequence, it marked it for what it truly was, one of the very best exploitation features.

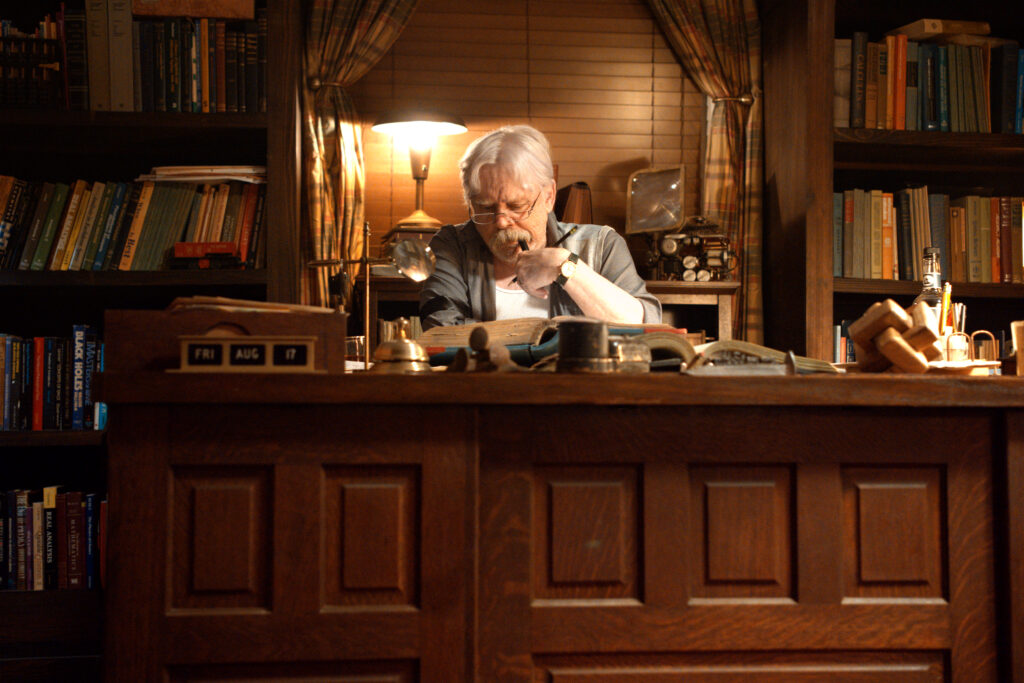

8) In The Mouth of Madness

The one movie that still proved that Carpenter had the ability to make a tremendous film during his ‘work-for-hire’ period of the 90s, In The Mouth of Madness is a great outlier in Carpenter’s filmography, a supernatural film that feels smart and surreal in its narrative, that many critics considered it pretentious during its initial theatrical run. Starring Sam Neill, in his return to the world of Carpenter after a villainous turn in Memoirs of an Invisible Man, as an insurance investigator, visiting a small town when looking into the disappearance of a successful horror author. Once reaching the town, the lines between reality and fiction begin to blur as Neill’s character begins to question his sanity, as this famous horror author seems to be able to bend reality to his own whim. The horror from this feature comes from the sense of the loss of free will, questioning how much free we will really have when something dictating our every move can be written. It is a clearly multilayered feature, questioning even what insanity really means, when one can be labelled as such when they are just acting outside of the regular order of nature put forward by society.

The texts written by the central author also make people insane, essentially showcasing Carpenter questioning the true meaning between crime and media, does what people view through film, television and fiction truly make them violent, or is it the people themselves that is to fault. There is a grand scale to the narrative that is so unlike Carpenter, with excellent creature designs and a genuine foreboding tone. Inspired by the works of H.P Lovecraft, and clearly with the author being designed to be like Stephen King, the film matches the scale of those two authors perfectly. The film even opens in media res, as Neill’s character tells the film’s narrative in a similar way to Lovecraft’s work, it’s a love letter to Lovecraftian horror that truly works.

7) The Fog

Started in 2020, and occurring annually on April 21st is Fog Day, a day where fans will watch Carpenter’s classic supernatural feature, The Fog. The fact that there is an entire day named after the film is a shocking one, especially after it received incredibly middling reviews during its initial theatrical run in 1980. In the years since, the film has garnered a cult following and an impressive re-assessment as one of Carpenter’s finest works, a drive which brought upon a critically panned remake in 2005. The film follows the day-to-day lives of the residents of a small coastal town in Northern California, whose lives are mixed up when a strange fog arrives in town. The fog brings ghosts linked to the past of the town, as the ghosts seek revenge on the children of the men that wronged them many years in the past. Dean Cudney’s cinematography is the star of the show of this feature, as Cudney shoots an incredible number of scenic shots of the coastal town, as it becomes encased in eerie fog, with the one brimmer of light coming from the tall lighthouse poking out in the distance. Carpenter makes the use of shadows to shoot the ghosts in complete murky light, more silhouettes than fully formed designs that add to the creepiness of the sequences, the fog hides them, and the lightning follows suit, but the little you see, of the zombie-like pirates makes for memorable creature design.

Carpenter’s strength here is the build-up, bringing together an incredibly well-cast set of characters that make the town feel alive, the tension palpable and makes you question the validity of the ghosts when both sides are almost human. Tom Atkins, Jamie Lee Curtis, Janet Leigh and Carpenter’s at-the-time wife, Adrienne Barbeau, all deliver strong performances. At heart, the movie is about the pain and sin that causes a town, a nation to be built, for each beautiful thing created, someone else is either stolen from or hurt for it to be made. 100 years on, the townsfolk celebrate their town with no idea what was done to create that very town, a topical message that could be conveyed to various aspects of American life, with a clear analogue to the pain and suffering brought to the Native Americans.

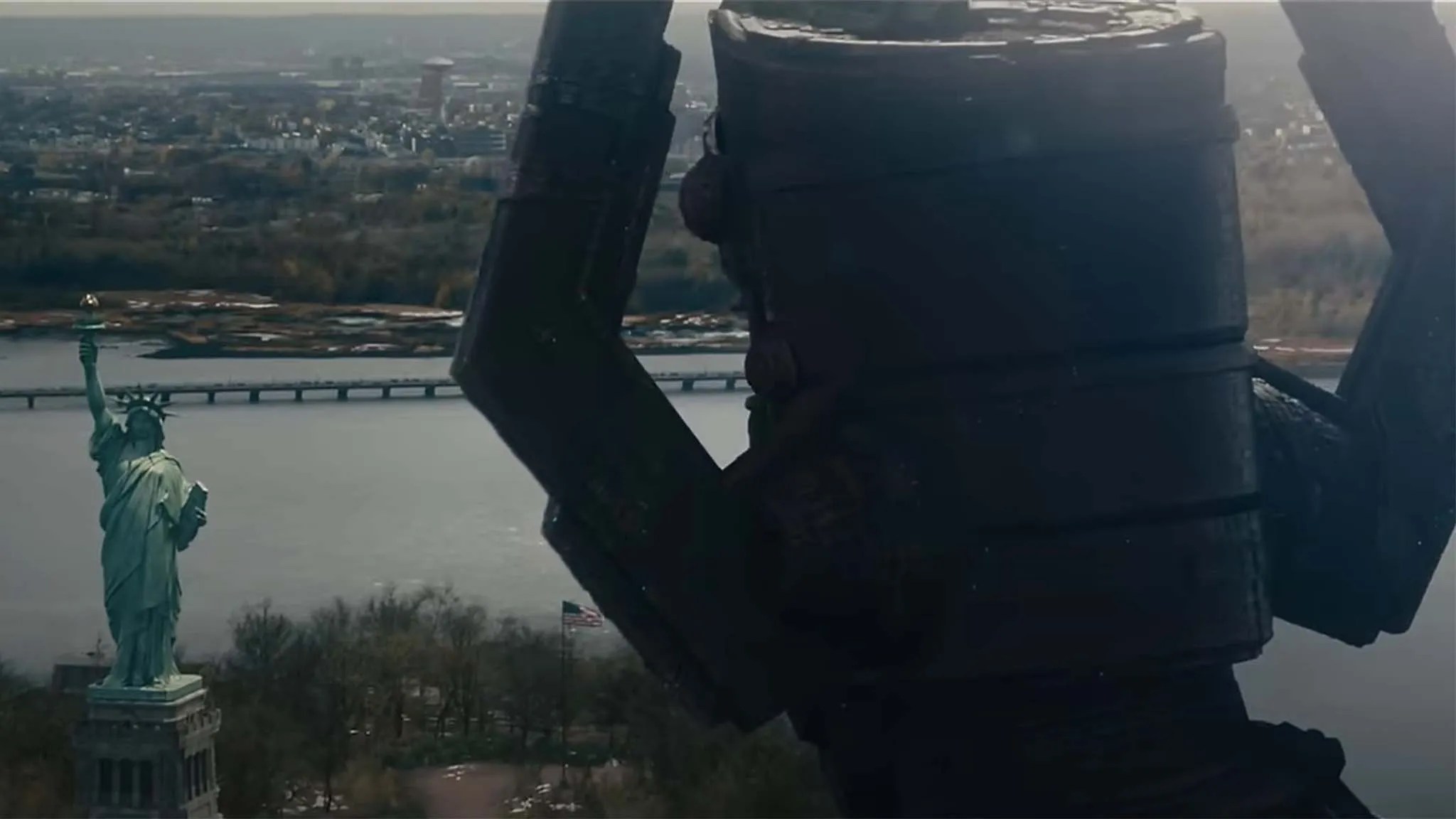

6) They Live

Carpenter’s career was characterized heavily by a series of films that were pessimistic in nature, even before he got to a feature focusing around Lovecraftian monsters controlling free will, and no film is more pessimistic than 1988’s They Live. A precursor to that before mentioned Lovecraftian feature, They Live follows a drifter who finds a special pair of sunglasses that reveal the secret truth of humanity. Putting on the sunglasses, they reveal to Nada, played by Roddy Piper, that the ruling class are aliens concealing their identities and rule the world through manipulating people to follow the status quo through subliminal messages across various forms of media. Based on the 1963 short story known as ‘Eight O’clock in the Morning ‘by Ray Nelson, the short story’s film rights were bought by Carpenter as he used it as a basis of his more developed script. His take came from how dissatisfied the director was with then-president Ronald Reagan’s economic policies, also known as Reaganomics, which was focused around increasing defence spending, slowed growth of government spending, reducing government regulation and tightening the money supply to reduce possible inflation. These economic policies were mixed in value, on one hand causing an entrepreneurial revolution, and on the other, the national debt tripling in eight years. The biggest outcome was the rise in consumerism in the country, another factor that Carpenter was spoofing in this feature, connecting mass consumerism as one of the major causes of drone-like personalities and American patriotism.

The film’s signature sunglasses sequences were shot with black-and-white photography, a filmic style which brings the sequences closer in line with war propaganda films during the second World War. The film has all the action movie quirks that makes films like Assault on Precinct 13 and Big Trouble in Little China work but mixed with an excellent amount of social commentary that makes every punch and gunshot come with a thematic purpose. It is a complete shame that the movie has essentially become the opposite of its thematic theming in popular culture, becoming a pop culture juggernaut in one of its central macho lines, and the film’s alien designs becoming synonymous with street art.

5) Escape from New York

Written originally in 1976 as a response to the Watergate scandal, the political turmoil of the time where American society did not trust their own president caused Carpenter to pen Escape from New York. The project would not be released until 1981, after the director had enough pull to begin production on such a risky movie after the smash hit of Halloween, and after Michael Myers actor Nick Castle was able to touch up the script with some humorous additions. The film mirrored a common trope for the time, concerning a grim and gritty look at New York City that perpetuated through the 80s with films like Ghostbusters and then into the 90s with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and a level of humanity drawn through humorous New Yorkers. Dealing with a near-future, a future which is ruled over by a forever president, and one where Manhattan Island in New York City has been caged off as a maximum-security prison. When Air Force One is hijacked and the President is kidnapped into the streets of New York, federal prisoner Snake Plissken is given twenty-four hours to find and rescue the President to be able to be pardoned for his crimes. Plissken is easily where this film shines, he seems like your typical action hero, but he is incredibly stubborn, angry and resentful across the film, speaking in low octave with almost growls rather than the typical one liner you would expect from an 80s action hero. Kurt Russell really shines here, playing against type as a gritty and serious action star after years of being a comedic actor.

He is known by every character in the film, building a mystique around him and the eventual excellent action sequences he will be able to pull off, and he has morals. The film twists the script on the typical hero-villain dynamic, Plissken is a shady individual but he’s a hero, while the people he is helping are clearly the villains. The President is the true antagonist, and the people who are keeping him hostage are just victims of a system that had put them down and refuses to give them the rehabilitation they deserve, a pure criticism of the American prison complex. It is a film which gives its viewers all the gritty action you would want out of your Hollywood blockbuster, but also enough to chew on under the surface, a bridge of both best worlds of cinema.

4) Big Trouble in Little China

20th Century Fox hired Carpenter to helm Big Trouble in Little China because of his reputation of being able to work incredibly fast, with the film facing a limited preproduction schedule of only ten to twelve weeks and rushed into production to beat a similar releasing film. The Eddie Murphy starring feature, The Golden Child, was seen as big competition for the studio, a film Carpenter was even offered to direct, sharing similar narrative threads, and having such a big star attached. Big Trouble in Little China was originally put into production as a separate film, mixing the action of the Western with the new popular sensibilities of the martial arts feature, but would be rewritten into being more modernised. This version of the script would be what enticed Carpenter to the feature, fulfilling his desire to one day direct a martial arts feature. The film, which continued Carpenter’s lack of success at the box office during theatrical runs, followed drifter truck-driver Jack Burton, who must help his friend Wang Chi rescue his green-eyed fiancée from criminals in San Francisco’s Chinatown. The green-eyed woman is important to the plot of an ancient sorcerer, who requires a woman with green eyes to marry him to be released from a centuries-old curse. An interesting genre blend of various tones and genres, from the American action movie, the comedy, mystical and supernatural elements and the martial arts feature, Carpenter’s high-flying feature has everything and has become a deserved cult classic in the years since release.

Kurt Russell returns to the world of the Carpenter feature, his role of Jack Burton inspired by the machismo of actors like John Wayne, but with an entertaining satirical edge. The film flips the American movie on its head, where once the American lead would have a foreign sidekick, Russell’s Burton is macho and cool, but he is a goof, and out of his element next to such strong leaders like Wang Chi. He is along for the ride in a narrative that spins around him, never through him, to the point that he is knocked out and misses the entire final battle. The failure at the box office of Big Trouble in Little China is what led John Carpenter back into the world of independent filmmaking, disillusioning him with mainstream Hollywood, where he would only come back for work-for-hire jobs. It is a shame as well that the movie put a pin in his big-budget career, because the film is one of the perfect summer blockbusters, feeling like a genre-blender at its best.

3) Halloween

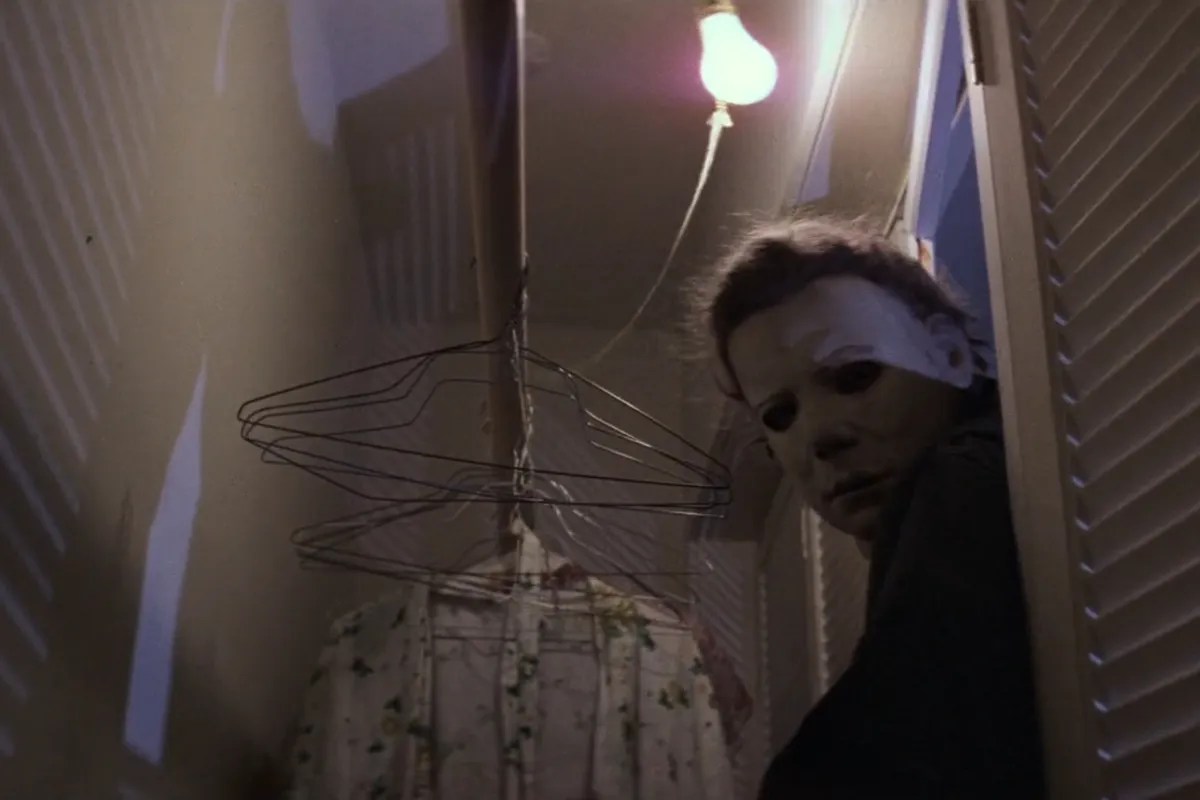

1978’s Halloween is an important release in the Hollywood zeitgeist for various reasons, from it being Carpenter’s first box office success, to launching the career of Jamie Lee Curtis, or being a big factor in the boom of the slasher movie sub-genre into the 80s and 90s. The slasher film existed beforehand, with 1960’s Psycho, or the double release of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Black Christmas in 1974, but the story of babysitter killer Michael Myers, who returns to Haddonfield after escaping a mental asylum to kill everyone who stands in his way, lit up the zeitgeist and proved the sub-genre could be a box office success. The final girl, the use of point-of-view shots of the killer, the chase sequence and the defining of sex as the cause of death in the feature would become staples of the genre and would define the entire Halloween franchise. To date, there are thirteen movies released in the franchise, with varied levels of involvement from series creator Carpenter, who essentially handed over the franchise after releasing the first feature.

The sequel’s script would be penned by the director, the third feature would move away from Michael to go through an anthology lens because of Carpenter’s insistence, and the director would return as producer and composer for Blumhouse’s requel trilogy, 2018’s Halloween, 2021’s Halloween Kills and 2022’s Halloween Ends. The slasher genre would follow the Halloween genre across the decades, with the initial boom coming from 1980’s Friday the 13th, which was a remake without the name of Halloween, to the genre being revived in the wake of 2018’s Halloween. This importance comes with a major reason; Carpenter’s initial Halloween feature is one of his very best. It is his very best score, with his most memorable motifs, and has two winning central performances by Jamie Lee Curtis and Donald Pleasence. The film’s central villain is incredibly intimidating and eerie, a feeling that many slasher villains cannot convey, with the eerie sound of his breathing being felt across various sequences. The film’s final shots linger on empty spaces, leaving the film on a menacing note, retracing each location from the film and proving that nowhere is safe, the boogeyman could be anywhere.

2) Starman

What starts as a science-fiction adventure with a creepy alien morphing sequence, soon becomes an emotional drama that stands as the biggest outlier in Carpenter’s filmography. The film, starring Jeff Bridges and Karen Allen, follows an alien arriving to Earth in response to the invitation found on the Voyager 2 space probe. The alien takes the form of a cloned body of a grieving widow’s husband, as the widow and the clone must take on a cross-county road-trip to send him home and escape the government who is after him. The film has been theorised to have been put into production as a response to the success of Spielberg’s ET: The Extraterrestrial and picked up Carpenter after The Thing failed at the box office because of audience’s being more familiar with positive alien features off the back of that previously mentioned Spielberg venture. The film, which went through at least six different script drafts, one where the signature alien flew during sequences, feels like an outlier in a career which is characterized heavily by films which feel pessimistic in nature. The film is hopeful and warm, a love story which uses its central science-fiction narrative to wow and surprise rather than to make the audience uneasy, a scene where Bridges’ alien revives a deer that has been killed by a hunter is one such powerful moment.

It is a road movie, with each character the central leads meet across their journey feeling warm and sincere, and even the central governmental forces allow the characters to go at the end. Karen Allen’s character feels like Carpenter willing himself into the narrative, a nihilistic character who feels only pain from the death of her husband, whose nihilistic tendencies are proven wrong by the film’s genuine pleasantness. Bridges received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor for the film, in a performance that feels so inhuman but never in a terrifying way, a perfect encapsulation of the fish out of water trope, he is charming in his eccentricities, and the central love story is moving and powerful. The movie ends on a terrific note, a loving final embrace leads Allen’s widow pregnant with a child who is both the child of her late husband and the alien she loved soon after, a moving final beat that encapsulates the tenderness of this film compared to each other Carpenter feature.

1) The Thing

No other film could be placed first on a John Carpenter ranking, The Thing is just his magnum opus. Based on the 1938 novella Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell Jr, which had already been adapted into the 1951 feature film, The Thing from Another World, the film is another Lovecraftian horror from the director. The film tells the story of a group of American researchers in Antarctica, who encounter an alien life-form that assimilates, then imitates organisms. The group is brought against each other, believing any one of them could be the signature ‘Thing’. The film is a perfect encapsulation of the feeling of paranoia and isolation, the viewer is along for the ride in trying to decide who is the Thing, the film leaving it up to the audience to catch up on the mystery as the characters figure it out together.

The setting of Antarctica also brings the isolation to the forefront, it is open plains of nothingness, encased in darkness which makes the characters cold and isolated, it is an eerie location which is used to its best effect. As mentioned previously, the film was a box office bomb when released in 1982 and was even slated by critics. It has since become a staple of the science-fiction genre, a creature feature with excellent creature effects by Rob Bottin, a film which is both disturbing and impressive in its use of practical effects. The eventual 2011 prequel, with the same name as its title, would try to compete with its CGI effects, but nothing can compare to the practical effects shown here, The Thing looks inhuman in each body modification it causes, but there’s always human elements to it, an eeriness to each form it takes. The film was initially given to director Tobe Hooper, and various other directors were considered after Carpenter briefly decided to leave the project to direct a passion project, which then fell through, but it is hard to see any other director helming the film. It’s Carpenter’s first big-budget feature, and cinematographer Dean Cudney’s as well. Only Carpenter could direct such a bleak film as this, playing the best to his nihilistic tendencies, as the situation feels hopeless and impossible, but balancing that with such well-realised characters.

Kurt Russell takes the lead once again, but with a character who is forced to lead, bouncing off such a wonderful supporting cast that is led by a wonderful performance by Keith David. When asked in an interview, Carpenter stated that the film is pro-human, in comparison to the original text’s pro-science exploration, or the initial film adaptation’s anti-science exploration. The film’s humanist approach to its storytelling has led to a series of discussions about the film’s thematic meaning, namely because of its creation during post-Cold War tendencies. The paranoia can be seen as a metaphor for the red scare at the time, with people not knowing who to trust in the wake of Communists being found across the country. The film is also exploring nuclear annihilation through mutually assured destruction in the wake of the Cold War, with the death of The Thing only being possible if both our lead characters die alongside it. However, the film’s end leads the film on a forever sinister note, a cliffhanger ending that only Carpenter knows the answer to, as both characters sit opposite each other not knowing if either or both are The Thing, a perfectly mysterious ending that leaves the audience thinking long after the film is finished.