The Monsterverse has been a staple of the American box office in the last decade, with 2021’s Godzilla Vs Kong being one of the few big budget features to make a massive profit during the COVID pandemic. Produced by Legendary Pictures and co-financed and distributed by Warner Bros Pictures, the franchise has been one of the only major cinematic universes that have been successful in the wake of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the franchise uniting the worlds of Godzilla and King Kong. Across five feature films, namely 2014’s Godzilla, 2017’s Kong: Skull Island, 2019’s Godzilla: King of The Monsters, Godzilla Vs Kong and 2024’s Godzilla X Kong: The New Empire, and two series, the film has grossed $2.525 billion at the worldwide box office, and will only continue to grow, with Godzilla X Kong: Supernova releasing in 2027. Known for its cinematic kaiju fights, the focus of the franchise is less on characters and drama, but more the conflicts between the massive monsters that call the franchise home. The character of King Kong belongs to Universal Pictures, first appearing as a novelization of the 1933 film that shared the character’s name, and appearing across various feature films, with remakes hitting the big screen in 1976 and 2005. Kong’s franchise was a relatively simple one and is easily reinvented for the Monsterverse to turn the character into a fighting monster. Godzilla, on the other hand, was most associated with the entire genre of Kaiju features, with one prior American film, Roland Emmerich’s 1998 film sharing the character’s name.

33 films have been made for the character across his time as a staple of Japanese cinema, released by the Toho company, as the monster battles various other kaiju’s, from King Ghidorah to Mothra, Rhodan to MechaGodzilla, the focus of the franchise has always been on the clash of giant monsters and the destruction that comes from that action. The initial concept of the clash between Godzilla and King Kong even comes from the initial Japanese Godzilla features, with 1962’s King Kong Vs Godzilla introducing the characters to one another, but also really reinforcing the routine of each Godzilla feature introducing a new monster for the titular character to face. The franchise is rooted in its own complex mythology, with films like 1968’s Destroy All Monsters acting as a crossover between various monsters featured throughout the franchise, and spinoff franchises that spawned from the franchise.

However, there is more to the Japanese productions of Godzilla then just climatic monster fights, the franchise is rooted in Japanese political and social turmoil. As easily Japan’s biggest film franchise, the films consistently reflect the period they are made in, reflecting Japanese life and the struggles that are happening socially and politically. The initial Godzilla feature, released in 1954, set the template for the franchise, following the reactions by the people and government of Japan as they attempt to take down a massive monster, a monster who is linked to the atomic past of the country and which triggers the fears of a potential nuclear holocaust. The conflict of World War II had not been kind to Japanese way of life, with the country joining the Axis powers, alongside Italy and Germany, to fight against the Allies. Though successful through a series of attacks, from the invasion of the Republic of China to the Military occupation of French Indochina, they also started the Pacific War, the biggest battle of the war after Japanese forces attacked multiple American and British positions in the Pacific.

Their successes would only lead to embarrassing defeats however, with the world power taking major losses in the Battle of Midway and facing the Soviet Union when they also declared war. The biggest loss would come on the 6th and 9th August 1945, when Japan was hit by two atomic bombs, over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, sent by the American armed forces, which killed between 150,000 to 246,000 people, mainly civilians. Only six days after the dropping of the second bomb, Japan would surrender to the Allies, and an American occupation of the country would begin, starting on September 2nd, 1945, and ending with the Treaty of San Francisco on April 28th, 1952. Godzilla would come out in the wake of all these events, only two years after America had left their posts in the occupation and would be seen as a reflection of Japan’s role in this nuclear conflict, and the potential annihilation that could come from continued nuclear tests.

The film opens with Godzilla destroying a Japanese vessel, a reflection of the most recent nuclear disaster that had happened in the country. Months before the film was made, in March of the same year, Japanese vessel Daigo Fukuryu Maru, was showered with radioactive fallout from the testing of the US’ Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb, at the nearby station of Bikini Atoll. This event led to the fear of Japan’s fish being contaminated by the nuclear fallout, with each member of the fishing crew being sickened, and one dead, and the boat’s catch becoming contaminated with radiation. This led to the emergence of a still-enduring anti-nuclear movement, which eventually became institutionalised as the Japan council against Atomic and Hydrogen bombs. Godzilla being a monster that is both mutated from nuclear bombs, and hails from the sea reflects this fear tremendously. The only way the characters can defeat Godzilla, in the end, is through the creation of the Oxygen Destroyer, a weapon that disintegrates oxygen atoms and causes victims to asphyxiate, and eventually dissolve, an item which is tested out in many horrifying scenes on fish. The item is dropped in the water, with its creator going with it to stop any attempt of it becoming a weapon of mass destruction, another weapon used on the aquatic life that had only just recovered from atomic testing. It is a grim ending, showcasing the only way to stop the atomic monster is to use another weapon that could cause as much pain and destruction.

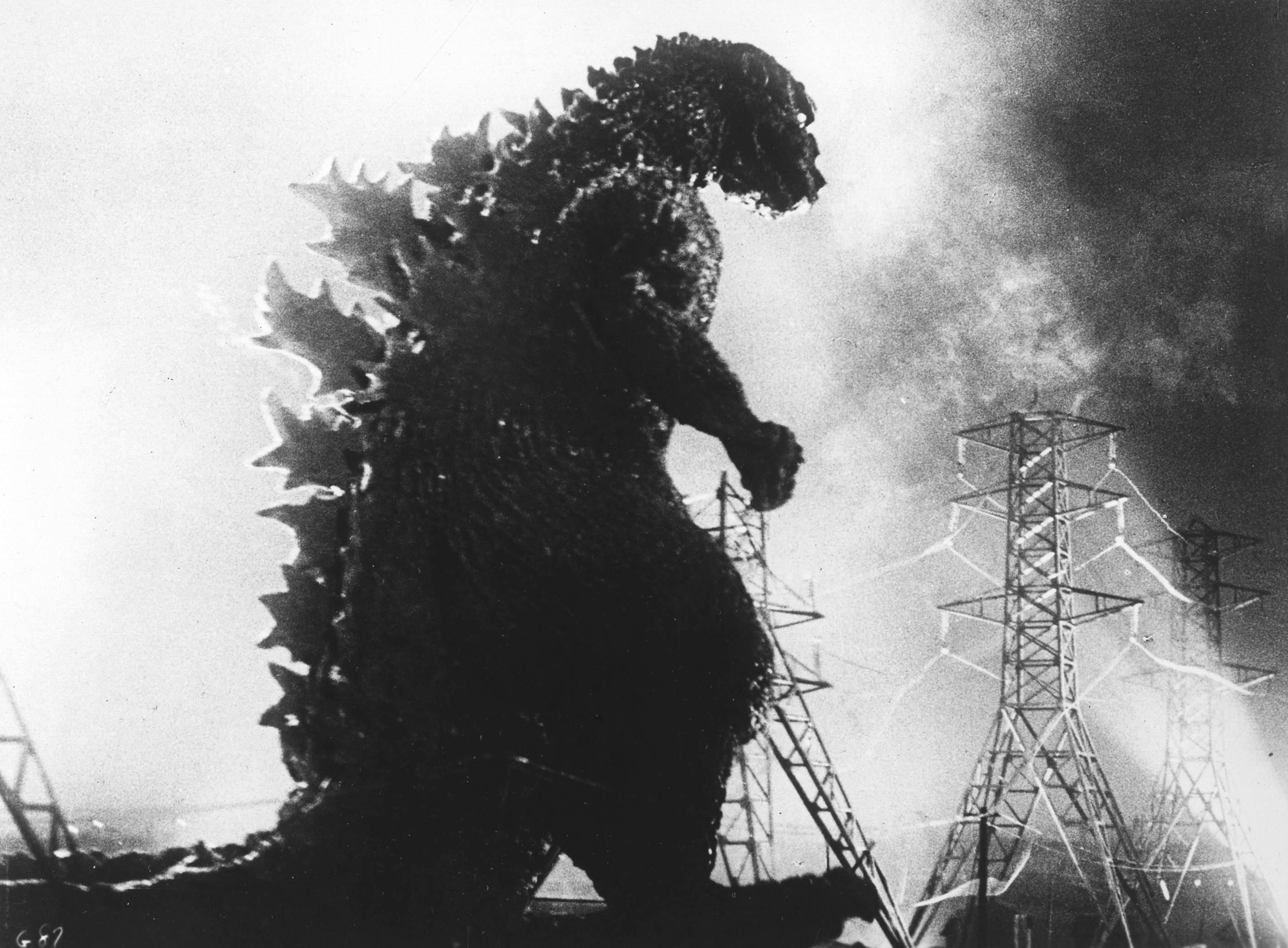

Godzilla, who would soon become a character akin to a superhero in the initial 70s stretches of features, becoming a protector of the innocent in child-friendly films like Son of Godzilla and All Monsters Attack, is shown as a frightening monster across the initial feature. His first actual appearance in the film, he is contained in darkness, with only his reign of terror being visible until his actual reveal later in the film. For a franchise that would soon be centred around action set pieces featuring people in costumes, the first film is incredibly bleak and contemplative. Most of the scenes feature people in boardrooms discussing how to stop the monster, or people travelling by town as they discuss the atomic past faced by the country. The film’s metaphors are laid out in dialogue, labelled out clearly in a thoughtfully manner which is both entertaining to view but also saddening and horrifying. A staple of Godzilla is used briefly in the film, the Atomic Breath, which would soon become an all-destroying beam which would be used as a killing blow to any other monster, is depicted as a beam which sets ablaze anything it encounters, smog filling the air.

After an attack on Tokyo, the hospitals are crowded with the maimed and the dead, many suffering from radiation sickness. Though seen as a being of pure destruction, nature’s attempt to punish man’s creation of the atomic bomb, the shared history of atomic destruction would cause Japanese viewers to feel sympathy for the terrifying monster. When being dubbed for the American release, 1956’s Godzilla, King of the Monsters, which featured new footage of Raymond Burr as an American reporter covering the events of the original film, removed the themes from the film in the dubbing. Though both featuring connections to Japan and atomic testing in their opening sequences, both 1998 and 2014 American Godzilla movies would quickly move the monster into America and forget these connections after. The 2014 film even moves the monster instead into being a prehistoric predator, a so-called ‘Titan’ which exists to battle to become nature’s champion. Godzilla’s connection to Japanese culture does not translate to American audiences, and once removed from so, becomes a generic monster to do battle with others.

Japanese Godzilla sequels would have a hard time trying to balance the monster fighting, which would be introduced instantly in the film’s sequel, 1955’s Godzilla Raids Again, and the political messaging that the initial film was known for. As mentioned previously, some films would focus more heavily on the fights, like 1965’s Invasion of the Astro Monster, or would be more comedy and family-friendly, like 1967’s Son of Godzilla. Some films, however, continue and develop more onto the themes of the original film. 1964’s Mothra Vs Godzilla, which unites the two monsters after starring in separate entries, 1961’s Mothra introducing that so called character, sees an exploration into greed and corruption. These themes, alongside military distrust and evil corporations would become a staple of the sequels, as the film involves Mothra’s egg being contained by a company in Japan. Rather than trying to save the egg itself, the film’s leads come to Mothra and ask for more, ask for its help in stopping Godzilla, using the egg as a bargaining chip. Mothra, who soon becomes more empathetic and willing to forgive, has a clear distrust for humanity after the atomic testing on its home, Infant Island, which left it as an atomic wasteland.

1971’s Godzilla Vs Hedorah sees the lead monster coming into conflict with a being made from pollution, reflecting the movement of fear for the country from one focused around nuclear disaster to one based around environmental fears of pollution. The film features some of the most graphic deaths in the series, as characters succumb to poisoning, their bodies dissolving when encountering the monstrous villain, and even sees Godzilla becoming burned and disfigured. Pollution is at the heart of the film’s central theming, but the victims becoming burned into becoming skeletons connects it heavily to the original atomic theming.

1984 and 1998 would see the franchise rebooted, both ignoring all sequels to the original film and being a direct sequel to that feature, with The Return of Godzilla and Godzilla 2000: Millenium respectively returning Godzilla to his force of nature identity. However, both rebooted series would return Godzilla to his heroic demeanour and to Kaiju fights soon after. 2016’s Shin Godzilla served as an update for the film’s metaphorical themes, transporting the character’s connection to the atomic bombings featured in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to being inspired by the tragedies of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster and the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. The film focused on Japanese politicians attempting to confront the foreign foe, with the film criticising the Japanese government, being unable to confront the threat as they fight themselves, reflecting the countries’ biggest threat as being from inside, rather than out. The most recent Godzilla feature, 2023’s Godzilla Minus One, works incredibly well as a modern reinterpretation of the original feature, exploring similar themes as that feature but through a directly post-war lens.

Godzilla is depicted in his most frightening form, with an atomic blast which can level a city instantly, destruction that has never looked more like an atomic bomb than ever before. Released the same year as Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, which explored the creation of the atomic bomb, the movies act as a conversation between each other, one focused around America’s involvement in the creation of such a weapon, and Japan’s exploration of the effects that the bomb had on everyday lives. The film’s newest theme focuses on its protagonist, who served as a kamikaze pilot during the war, who is looked down upon by his community because of his inability to die in conflict and do his role.

Bushido was a central ideal in Japanese way of life, connected to the samurai period in the country, and being reinforced as the honour to die in battle during the second World War. The lead of Godzilla Minus One is suicidal, wanting to die in battle fighting Godzilla and bring honour back to his name, as he faces the conflict between wanting to live and die. The film is a clear critique of the government’s argument that persuaded many to take their life during the second World War, using Godzilla once again to hit home a sensitive topic for the people of Japan.

All in all, Godzilla is one of Japan’s biggest touchstones, a cinematic franchise that is so deeply rooted in the social and political conflicts that have faced the country across the years. The initial feature rooted itself in the nuclear fallout of the second world war, using Godzilla as a metaphor for the events of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Subsequent follow-ups would continue to develop on these themes, alongside explorations into bushido, pollution and the earthquake-tsunami that occurred in 2011. The character has become one of the countries’ biggest exports, appearing in a series of films by Legendary Pictures from 2014 to the present day, a series which loses its connection to the film’s thematic roots, and becomes boiled down to monster fights. This is simply because Godzilla is Japan, and removing the monster from so loosens his impact.