On release in 1973, audiences waited out in long lines for Warner Bros biggest film since The Godfather, a film which was reported to have some of the strongest audience reactions to this date. Various viewers reportedly fainted during sequences, a New York citizen was reported to have miscarried, and one man was carried out in a stretcher after only 20 minutes. Nausea was frequent, and Catholic viewers, including both people who had lapsed in their faith and current faith practisers, stated that they experienced spiritual crises before and after watching the film. In the UK, the film drew protests from the Nationwide Festival of Light, a Christian public action group, and once released on home video, the film was withdrawn from being available after the passing of the Video Recordings Act in 1984, which sought to ban so called ‘video nasties’. This film, which gained so much outrage and paranoia, is The Exorcist, director William Friedkin’s supernatural-drama based on screenwriter William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel of the same name. The Exorcist has become an iconic horror feature in the time since, spawning a franchise and influencing the future of the horror genre in subsequent years, after grossing $193 million worldwide, and a lifetime gross of $441 million after re-releases. The film spent decades as the highest grossing R-rated film (adjusted for inflation), until being de-throned by Stephen King adaptation IT in 2017, and became the first horror film to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture, with Blatty winning the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay and the production crew taking home the Academy Award for Best Sound.

William Peter Blatty’s original novel was inspired by the one of the very first cases of demonic possession known to the public, a phenomenon that would being more widespread in the years after the release of the Exorcist. Exorcisms, performed by the Catholic Church, were a low commodity in the years before Friedkin’s film, but cases reported to the Church became more frequent after the film’s release. It would even get to the point that demonic possession would come to the courts in 1981, with the trial of Arne Cheyenne Johnson, who claimed that he was possessed by the devil when committing murders. The trial would go on to be the basis of the third Conjuring film, The Conjuring: The Devil Made Me Do It in 2021.

Blatty’s basis would be a lot less mainstream than Johnson’s case, with the novel being based on a series of exorcisms performed on an anonymous boy by the attending priest, Raymond J. Bishop, and under the pseudonym ‘Roland Doe’ or ‘Robbie Mannheim’. It was claimed that the boy became possessed after coming into possession of a Ouija Board, which would become a small plot point in Blatty’s screenplay. So little was known about the case during Blatty’s discovery of the events, that it took until December 2021 for the American magazine, The Sceptical Inquirer, to report the purported identity of the boy as Ronald Edwin Hunkeler. Blatty’s signature drive to craft the novel came from seeing Roman Polanski’s adaptation of Rosemary’s Baby in 1968, being drawn to the film’s ability to keep the audience unsure whether Rosemary’s concerns for the supernatural nature of her baby were genuine or unfounded. He was, however, unhappy in the ending, believing the reveals to be shlocky in nature, and was determined to craft a novel that bridged the world between realism and the supernatural convincingly.

This becomes the route of the narrative thrust of both the novel and the film adaptation. The Exorcist follows the mysterious demonic possession of eleven-year-old Regan MacNeill, the daughter of a famous Hollywood actress. Her mother, Chris, pursues every angle to try and explain what is wrong with her daughter, and after scientific means fail her daughter, she recruits two priests to try and exorcise the demon. Those priests come in the form of Father Damian Karras, a priest who has lost his way after the death of his mother, and Father Lankester Merrin, who has done battle with the demon before. The novel and film retain the same basic plot developments, but Blatty’s screenplay narrows the focus down to the key plot points and characters that make up the narrative crux. The time frame of the events is shortened, and characters like Chris’ staff, Dennings and Regan’s father are removed entirely. A lot of the most horrifying content of the novel was also toned down in scripting, mainly the sexual aspects, once it was clear an age-accurate actress would play the eleven-year-old character. Blatty’s screenplay also foregoes the ambiguous nature of the novel’s perception of the supernatural events, with each occurrence of Regan’s supernatural abilities being paired with a reference to a real-world case where the root of the problem was revealed to be scientific in nature. Outside of Karras’ initial concerns over the validity of the claims, the film version removes the sceptical perspective entirely.

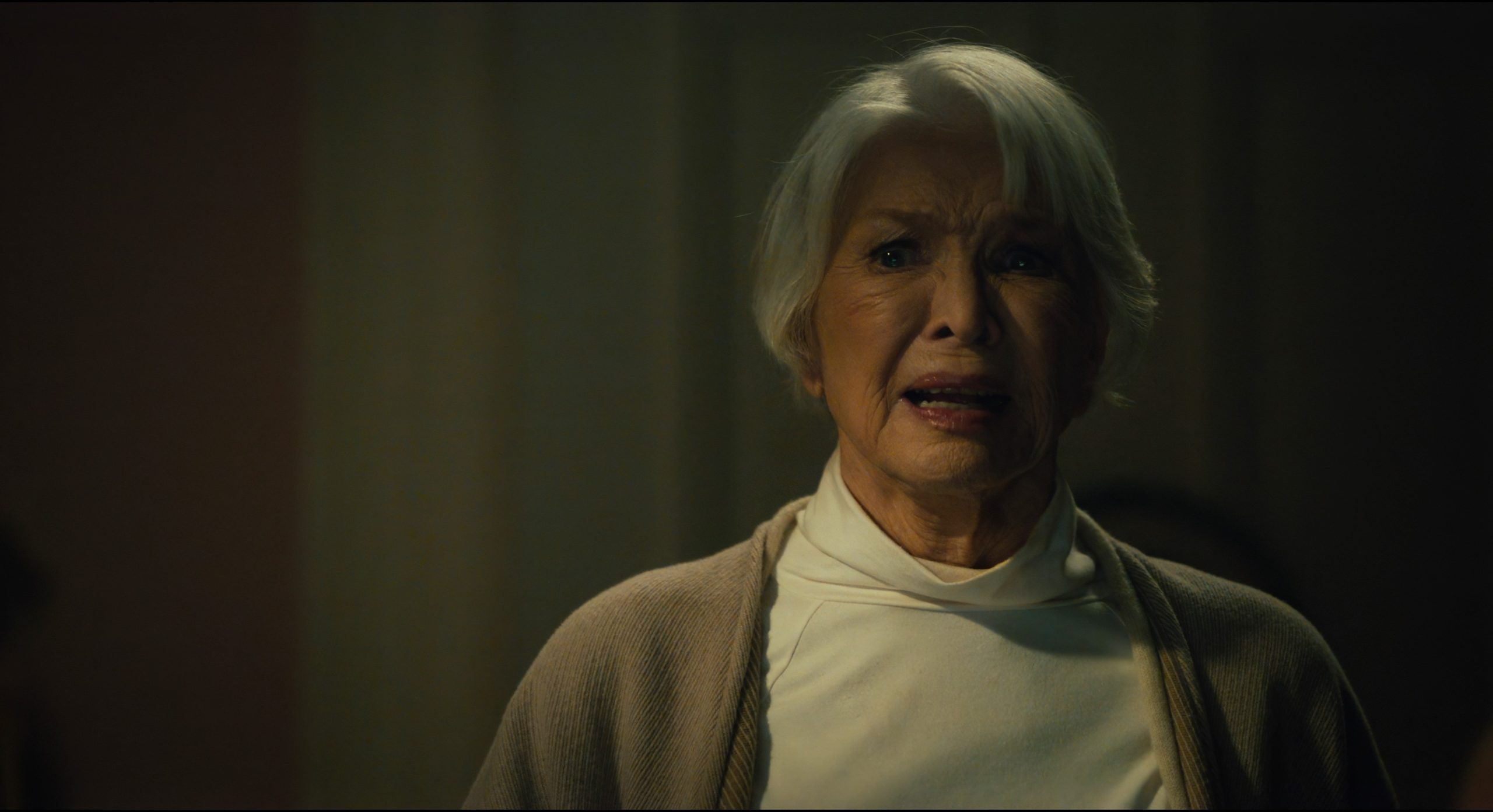

This lack of scepticism leads the emotional throughline of the film’s narrative, a mother’s pursuit to do anything possible to save her daughter. Chris is a famous actress and moves herself and her daughter to a new home for an upcoming role, and this movement leads to an isolation for her character instantly, and Blatty’s screenplay pairs the small-town drama aspect with horror perfectly. The film never gives the viewer a perfect answer for how Regan becomes possessed, it could be the Ouija board, but its never told for sure, and this mystery thrusts Chris into action. She takes Regan to every scientific expert she could think of, with the film displaying these scientific machines as cold and terrifying, with many audience members finding the angiography sequence to be the film’s most unsettling moment. When all the natural means fail her, the film crosses over into the supernatural with her, placing her complete faith in the unknown and to the two priests that could save her daughter. Ellen Burstyn delivers a moving performance across the film, capturing a vulnerability and an openness to a mother who will do anything for her daughter, and the slow-moving nature of the opening allows the audience to gain a connection to the bond between Chris and Regan, and even more so Burstyn and Linda Blair.

The balance between realism and faith also comes in the character of Karras, played by Jason Miller. Karras is a complex character, he is railroaded by his grief, losing faith in God after he seen his mother go through so much pain before death. It’s this pursuit of meaning to regain his faith which holds together his arc. He falls under the pull of his grief when Regan’s possessed self makes fun of his mother, but he ends the film allowing good to prevail. His fall from the window allows him to remove the demon from the mortal plane, and he knows that in his death, God will accept him once again. Miller’s performance matches Burstyn’s, he is calm and collected, the pain coming from his eyes and his facial expressions, but he conveys a sense of warmth and kindness. These two central performances convey why The Exorcist is such a compelling film, it bridges the world between horror and drama so perfectly, it’s a movie about a woman trying to save her child and a man trying to regain his faith, with supernatural undertones to compliment those narrative elements.

That is not to say, however, that The Exorcist is without its frightening scares. What once was known as ‘one of the scariest films ever made’, may feel less frightening to a modern audience who are used to supernatural clowns and nuns, but the film’s horror still works frequently. Scenes like the crucifix masturbation scene also works as a scene to both frighten and make the audience uncomfortable, shooting the sequence head on to make the audience feel like they are also in the room. Friedkin’s direction, who was hot off the success of 1971’s The French Connection, which he won the Academy Award for Best Picture and Best Director for, makes the film feel like a pseudo-documentary. The audience feels like a fly-on-the-wall of the events taking place, as the natural lightning and authentic set design gives the film the air of realism. The supernatural aspects are aesthetically toned down compared to the novel, so when they do occur, they hit harder than if the scares were frequent and expected. The head twist sequence is a pure example of this, its terrifying because it is the only attempt at doing something so incredibly outlandish in the film’s runtime.

A similar experience was exercised from the film, a spider-walk sequence where Regan comes down the stairs in a creepy crawl, ending with a shot of Regan with a blood-soaked mouth. Blatty and Friedkin disagreed on various aspects of the film, namely the crucifixion masturbation sequence, and this was one sequence which Friedkin removed because of Blatty’s insistence. The scene stayed hidden for years, with many people arguing whether it even existed in the first place but was soon found by film critic Mark Kermode in the Warner Bros. archives when researching his book analysing the film, and the scene was reinstated in the 2000s director’s cut. The director’s cut was also used to re-emphasise one of the creepiest sequences of the film, the brief flash of the true face of the demon. The demon would not be named properly until the sequel, but his form would appear as both a face flashed on screen during Karras’ dream, and as a statue found by Merrin in the film’s prologue. The directors cut made use of this subliminal flash and placed it more commonly across the film, placed in frightening moments to give a more dream-like feel to the film.

The legacy of The Exorcist is a hard thing to describe completely, it was a wildfire of a film which proved that horror films can be taken seriously, making more A-list actors interested in starring in horror features. A massive trend followed the release of the feature, with studios allocating larger budgets to films that fit into a similar niche for the genre, namely 1976’s The Omen and 1979’s The Amityville Horror. Exorcism features would also become a trend in the coming years, a sub-genre in horror that still dominates the box office today, with The Conjuring franchise focused on similar genre tropes started by The Exorcist.

The film also spawned a franchise, followed by The Exorcist II: The Heretic in 1977, a film made without the involvement of either Friedkin or Blatty, and would stall the franchise for another 13 years after failing critically. In response to the negative response to the sequel, Friedkin and Blatty began work on their own sequel, which Blatty turned into his sequel novel Legion, once Friedkin departed from the project. Legion follows side characters, Detective Kinderman and Father Dyer, from the original novel, who become involved in a criminal case with a revived serial killer. The novel became the basis of Blatty’s screenplay for The Exorcist III, which he would also direct. Two attempts at a prequel following Father Merrin’s first encounter with Pazuzu would follow next, with Paul Schrader hired first and then replaced by Renny Harlin to replace him as director. Warner Bros would release Harlin’s Exorcist: The Beginning in 2004, and after becoming a critical and commercial failure, Schrader’s Dominion: Prequel to The Exorcist would be released in 2005. The latest attempt to keep this franchise alive, after a two season TV adaptation on Fox, would come from Blumhouse, after acquiring the rights to the franchise for $300 million dollars, with the release of The Exorcist: Believer in 2023. The two sequels would be scrapped after its failure, and a Mike Flanagan-directed reboot is currently in the works for the studio. As a franchise, it seems that The Exorcist floundered, but it only proves how monumental the original is, it was a lightning in a bottle film, and that is hard to capture afterwards.

Willaim Friedkin and William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist is a tremendous undertaking of a horror feature, an important film that legitimised the horror genre for the mainstream public. It is a completely accurate adaptation of Blatty’s original novel, with a more streamlined approach that could be argued to make the story even better. What makes the movie work so well, and what the franchise since could not recapture, is the balance between the horror and the drama. The movie, at heart, is about the distinction between science and faith, and the human drama of a man losing his faith and a woman trying to save her daughter, wrapped in a horror story focused on a demon.

Leave a comment