In the modern landscape of cinematic franchises, the cinematic universe is the new fad that has took Hollywood by storm. From comic book franchises belonging to the worlds of Marvel and DC, the battling titans featured throughout the shared Godzilla and King Kong universe or the haunting worlds featured in the Conjuring Cinematic Universe, cinematic universes are the newest evolution of franchise cinema. When once a franchise would just be made up of connected sequels or prequels, cinematic universes dwell in an area between, featuring various sub-franchises that connect through superficial connections but are still largely disconnected enough to have sequels and prequels of their own. Though seemingly coming to prominence because of the success of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, one connected universe predates the fad by almost 80 years, and that universe is the Universal Monsters.

It is up to debate how many movies can be classed as part of the Universal Monsters universe, ranging to up to 60 titles, and ranging from the years 1929 to 1960. Most of those 60 titles are standalone horror, mystery and science-fiction films that are mainly brought together by being under the Universal Pictures brand. Where the cinematic universe mainly comes together is through its core franchises, which will be the focus here. Dracula, The Wolf-Man, Frankenstein, The Invisible Man, The Mummy and The Creature from the Black Lagoon are where the shared universe comes to ahead, serving each as their own horror franchises, but also as a connected universe in an era where that was uncommon. Through the House of Frankenstein, House of Dracula and Abbott and Costello meet movies, these separated horror franchises come together in ambitious crossovers that predate some of the most celebrated crossover films that are common today. Here is a brief look at these franchises, and the crossovers that eventually come:

Dracula

Years: 1931-1943

Featured Films: Dracula (1931), Drȧcula (1931), Dracula’s Daughter (1936), Son of Dracula (1943)

Originally published in 1897, Bram Stoker’s classic horror novel was sought after for an adaptation for years before Universal got their hands on it, from F.W.Murnau’s unofficial adaptation, Nosferatu, to a broadway show. Following the events of the famous novel near-faithfully, the film follows Count Dracula, played by Bela Lugosi, an immortal vampire who travels between his home in Transylvania to England, looking to feast upon new victims and drink their blood. The film owes most of its success to the original novel it is based upon, but clearly draws upon clear influence through Nosferatu. An original scene that was only featured in Murnau’s adaptation of the novel is featured here as well, where the visiting Harker pricks himself and draws blood, Dracula skirting into shot as he attempts to remove his temptation. That’s not the only thing that Dracula, and the overall Universal Monsters juggernaut, owes to Nosferatu however, as its clear to see that the visual style, and the overall visual style of the German Expressionist movement, influenced the universe’s visual style heavily. Originally confined to Germany in WW1, the German Expressionist movement sought to reject reality in favour of the artist’s creative vision, favouring to use heightened performances and visual distortions. The gothic backdrops of the Universal Monsters are a clear highlight of this influence, through the use of fog and darkness as distortions, structured sets that blend the realism of gothic architecture and the horrific unknown like Castle Dracula in Transylvania, and expressive performances, like the ones featured here, with various shots focusing on Lugosi’s eyes. He is shot commonly in shadow, with only his eyes highlighted by any light, drawing attention to that fierce glare. This attention drawn to the look of the character highlights the iconicity that comes with this version of character, the first adaptation to keep the human-look of the character from the novel, and would become a clear influence on all future adaptations.

Even though Bela Lugosi became synonymous as the look of the character, the actor would not return for either of the sequels, only returning once across the future of the franchise, returning for 1948’s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. The same year the actor originally played this character however, a Spanish adaptation was also in the works, using the exact same sets and the same story, only allowed to go into production for night shoots after the more commercial version was finished for the day. An actual sequel came 5 years later, after the popularity of the re-releases of Frankenstein and Dracula brought Universal new confidence in their horror titans, with the release of Dracula’s Daughter in 1936. Following up on the death of its title character, this sequel’s only connective tissue was through the return of Van Helsing, now renamed Von Helsing, but retaining the same actor. The film retains some of the thematic elements of Murnau’s Nosferatu, now mixing the gothic locations with a narrative involving a troubled and saddened villain. Nosferatu is an evil protagonist in the original film, but is looking for love, even if it comes from a terrible place. Dracula’s Daughter, portrayed by Gloria Holden, is looking to remove the influence her father and the vampirism has over her, even if it means dying.

She only becomes the villain, in the climax, after falling further under the power of the vampirism, finding love in the film, even alluded to be lesbian-in-nature, but only for it to be tragic for her. Son of Dracula, its 1943 follow-up, nixes this thematic consistency and any narrative connective tissue, in order for a straightforward remake-like sequel following Lon Chaney Jr as somehow revived Count Dracula, looking to drink blood once again. This begins a long-running inconcinnity between franchises and their sequels, dealing with themselves as more like standalone entries than a connected franchise. The biggest consistency between them all is forever their visual style, because even Son of Dracula, though retaining no narrative ties, still features the visual flair of the mist, this time coming from the swamp.

Universal’s Dracula would go on to influence the character for decades to come, through Hammer horror’s own Dracula series and other big screen adaptations, like Francis Ford Coppolas version. Universal themselves would attempt twice, in the modern era, to bring back their big-screen vampire, through rebooted 2014’s Dracula Untold and semi-related spiritual sequel, 2023’s Renfield.

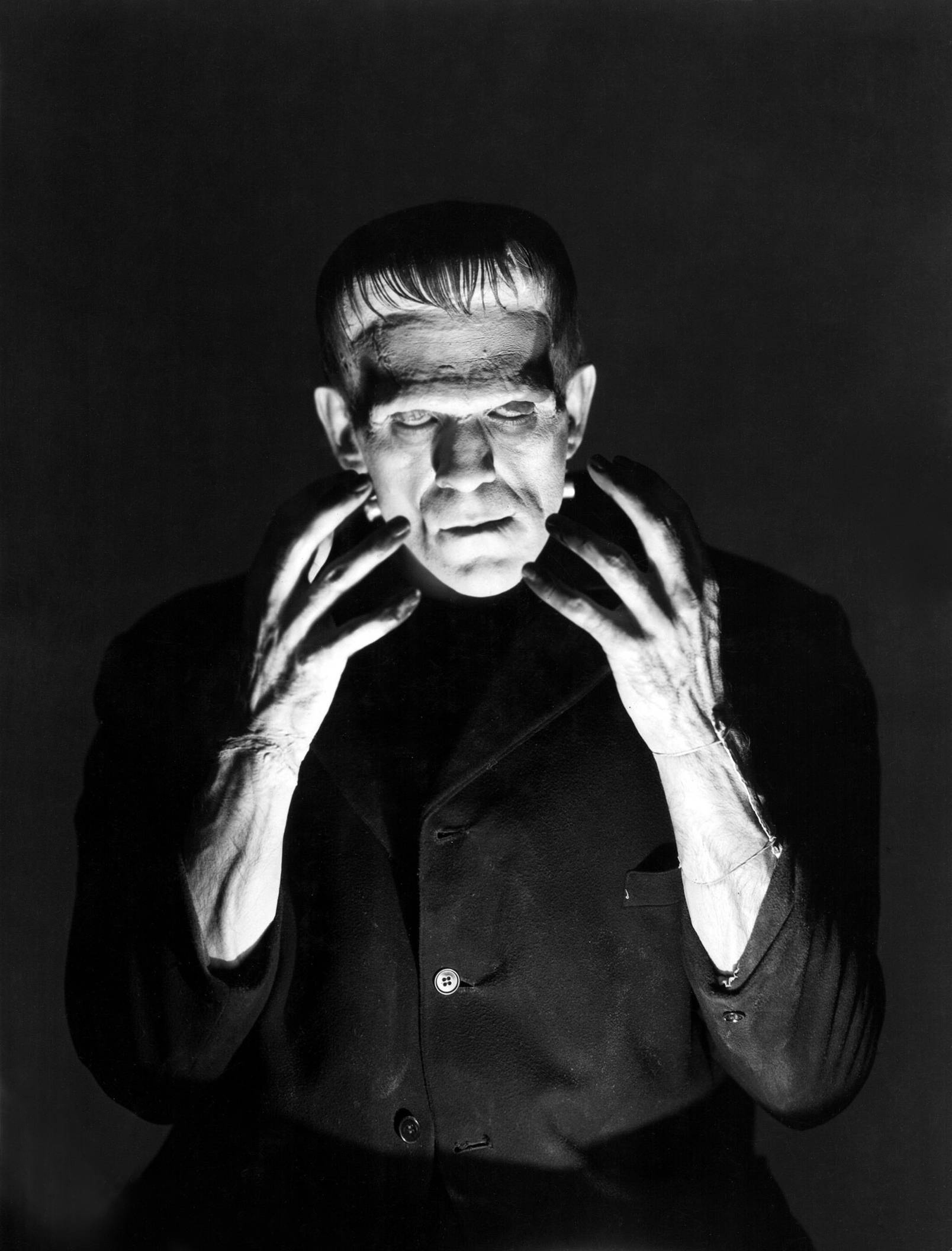

Frankenstein

Years: 1931-1942

Featured Films: Frankenstein (1931), Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Son of Frankenstein (1939), The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942)

Just like the former Dracula franchise, 1931’s Frankenstein and its following sequels, would become synonymous with the character in the coming years, being the first major adaptation of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel of the same name. The film shares the similar narrative plot breakdown of the original novel, following Henry Frankenstein (known as Victor in the novel), portrayed by Colin Clive, a brilliant scientist who attempts to recreate life by digging up dead bodies and grafting them together into a new being. Once brought to life, the monster, played by Boris Karloff, starts a reign of terror across the village, with a mob forming to take him down. The film only serves as a loose adaptation of the novel its based on, essentially being only a adaptation of the first half, with a lot of the removed moments being instead adapted into the follow-up, 1935’s The Bride of Frankenstein. This film seemingly is based on a subplot of the novel, with Frankenstein’s Monster demanding Victor to create him a wife or he will kill his wife, and in this version, Henry Frankenstein actually commits to the idea and creates the bride, portrayed by Elsa Lanchester. The reason for this difference between versions is through the depiction of the Monster. In the original novel, the Monster begins to develop intelligence after being homed by a friendly blind-man, and slowly begins to understand the evil of humanity through his experiences, eventually becoming a cold-blooded murderer after Victor refuses to create his bride. The Monster of the Universal film instead is dumb and brutish, easily able to fall under influence and more acting out of fear than anything. The reason the town hates him is because he misunderstands a game with a young child, accidentally killing her and causing himself to be villainised by the frightened mob. One version of the monster acts out of his own directives, while the other is manipulated and misunderstood.

The following sequels to these two initial films do not adapt anything from the original novel however, instead having connective tissue to the franchise through the use of the monster himself, the family of Frankenstein and the terrified mob. Both 1939’s Son of Frankenstein and 1942’s Ghost of Frankenstein reveal separate sons of the late Henry Frankenstein, Baron Wolf von Frankenstein and Ludwig Frankenstein. The films’ deal with the supposed curse of the Frankenstein family, and the overall paranoia of the town after the initial assault by the monster. When returning home and coming into ownership of the Frankenstein estate, Baron is warned by the people of the town to not revive the Monster, brought to the court as they show their fear. In the very next film, Frankenstein’s Monster, now played by Lon Chaney Jr after Karloff portrayed the character for the final time in Son of Frankenstein, and new ally Ygor, portrayed by Bela Lugosi, are ran out of the town as they make their way to a new home. Once arriving to their new home, they soon run into the same problem again as their monstrous appearances make them public enemies to the local townsfolk and are formed into a mob against them. Though not based on any existing material, these subsequent films still tie themselves thematically to the themes of the novel, with Ygor essentially being the replacement of both a villainous Monster and a more scientific variation of a Frankenstein. He is essentially the monster’s master in these films, and the final film ends with Ygor placing his brain in the body of Frankenstein’s monster. However, his brain is not a match for this body, rendering him blind. This massive change is never mentioned again after this film, with Frankenstein’s monster returning to his regular state by his next appearance in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man.

Universal has never made their own remake of their version of Frankenstein, though this rendition of the character has become the blueprint for all future filmic appearances of the character.

The Mummy

Years: 1932-1944

Featured Films: The Mummy (1932), The Mummy’s Hand (1940), The Mummy’s Tomb (1942), The Mummy’s Ghost (1944), The Mummy’s Curse (1944)

The first Universal Monsters franchise not to be based on pre-existing material, The Mummy takes the horror away from gothic locations and instead to the tombs of Ancient Egypt. The initial film of the franchise follows Imhotep, played by Boris Karloff, an undead mummy who comes back to life after being found by a team of archaeologists. Once revived, the undead mummy attempts to find his long-lost love, who he believes has also been reincarnated. The franchise straddles the line between the worlds of German Expressionist horror that the Universal Monsters are commonly situated in and the worlds of historical-adventure films with tombs, explorers and traps. The initial film is fairly standalone in comparison to the overall narrative of the sequels, the sequels instead centring around the revised corpse of Kharis, played by Tom Tyler in 1940’s The Mummy’s Hand, and Lon Chaney Jr in 1942’s The Mummy’s Tomb, 1944’s The Mummy’s Ghost and 1944’s The Mummy’s Curse.

Here, the franchise comes together with a central narrative, with Kharis being a very different monster compared to Imhotep. Kharis still follows the basic same narrative that Imhotep involved himself with, a revived monster that is after his own reincarnated love, but he lacks the control over that narrative that Imhotep had. He is mostly a mindless monster in his four filmic appearances, instead being controlled by the actual villains of the film, enchanted to do their bidding. Imhotep also looks more human, while Kharis resembles the more typical depiction of a Mummy in popular cinema, wrapped in bandages and fossilised. The later movies of the franchise also move into a direction of moving the action to the regular gothic locations of the Universal Monsters and abandon the Indiana Jones-style adventure side of the franchise. This leaves this franchise as being inherently two-sided, an opening film which sets the standard and the narrative beats that the franchise uses as a blueprint, and a closing two-final films that largely abandons these to follow the formula that made up films like Dracula and Frankenstein.

The franchise would return to its action-adventure roots with the Brendan Fraser-starring reboot in 1999, followed by two sequels, 2001’s The Mummy Returns and 2008’s The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor. It would soon also be rebooted again with 2017’s The Mummy, staring Tom Cruise.

The Invisible Man

Years: 1933-1944

Featured Films: The Invisible Man (1933), The Invisible Man Returns (1940), The Invisible Woman (1940), Invisible Agent (1942), The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944)

Loosely based on H.G.Wells’ 1897 novel of the same name, the Invisible Man franchise sits as an extreme outlier in the Universal Monsters, adding in another genre to the mix, science-fiction. Each subsequent film moves further and further away from the horror genre, with 1940’s The Invisible Woman being able to be described as both a women’s film and a comedy, while 1942’s Invisible Agent sits perfectly in the spy-espionage genre. The original film blends the worlds of horror and science-fiction the most comfortably, following Jack Griffin, played by Claude Rains, a scientist who has managed to turn himself invisible by a strange experiment. Hiding out in a village house, covered in bandages, the experiment slowly starts to take over his mind, transforming him from harmless scientist to a monster. In the process, his fiancée comes to find him, hoping to remove this new found superiority that has plagued Griffin’s mind. In the build up to the eventual complete takeover of his mind, the film does include elements of slapstick, that seems to connect to the eventual comedy take on the subject matter. His invisible antics begin as harmless pranks, with his furthest level of violence being knocking one of the home-owners down the stairs. Scenes including one where Griffin dances around in just his pyjama pants, show both the sense of humour of the central villain and the comedic lens the franchise can run with using the impressive special effects. Soon, he recruits a former comrade to help him commit various murders, and leads to him having one of the highest body counts of any of the Universal Monsters, derailing a train, leading to the death of over 100 people.

Claude Rains, and Jack Griffin, would not return for any of the Invisible Man sequels, perishing at the end of the initial film. This marked the beginning of the most fragmented franchise that made up the Universal Monsters, with future films struggling to find connections as easily as just reviving Frankenstein’s Monster or Dracula, as the others could easily do. Both 1940’s Invisible Man Returns and 1944’s Invisible Man’s Revenge’s titles seem ludicrous when seeing that they are not the same invisible killer. Returns has the connection through the invisibility serum being from the family of Griffin, but Revenge, a movie that seems to try to return the franchise back to form after comedy and spy entries, has no connection. Even the spy entry, a film where the invisible formula is used to take on villains featured as the Nazis, features a connection through the lead character, Frank Griffin, being revealed to be a relative of the original Griffin. The lack of consistency through the narrative leaves this franchise feeling disconnected, and each film feeling less like a sequel and more like a reboot, re-treading similar narrative beats, from the slapstick beginnings to the serum’s mind-altering end. The Invisible Woman only serves to confuse things further, feeling like a spin-off, removing the melodramatic elements that made up the prior films in favour of being a screwball comedy where a woman gets payback on her ruthless boss. When a franchise has so many mixing genres at play, it comes across less like a connected franchise, and more like a skeleton of what could be.

The Invisible Man would soon be rebooted in 2020, directed by Leigh Whannell, nixing the science-fiction formulas for a high-tech invisibility suit, and revolving its plot around domestic abuse.

The Wolf Man

Years: 1941-1943

Featured Films: The Wolf Man (1941), Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man (1943)

The shortest franchise of the core Universal Monsters, The Wolf Man only features in two films revolved around his own name, and the second is the first crossover of the cinematic universe. The initial film follows Lawrence Talbot, played by Lon Chaney Jr, as he returns home to bury his brother and hopefully resolve the fractured relationship with his father. In the process, he meets a new romantic interest and after being attacked by a wolf, slowly becomes the monstrous Wolf-Man. The werewolf can be seen as an implied metaphor for various factors across the runtime of the film, but mainly as a metaphorical look at man’s attempt to control. Talbot is very full-on when trying to pursue his romantic interest, a woman who turns him down completely, and only initially goes on the date with him because she brings a friend with her. Here, on the date, she also tells Talbot that she is engaged, but that does not make him stop the pursuit at all. He’s a man who seems to not take no as an answer, a man who seems to enjoy to have control in his life, and that is thrown all away the minute he cannot control his own body when transformed.

He becomes this way because he comes into contact with an attacking werewolf, an unpredictable part of nature that only becomes worse because he attempts to take control. A friendly gypsy gifts him a protective charm that will help him not transform, but unwilling to believe in the power of nature, he dooms himself by giving it away, refusing to place his role in the natural world. He soon learns, in 1943’s Frankenstein meets the Wolf Man, that he cannot die through regular means, and the only way out seems to be the unnatural world of Victor Frankenstein. Through attempting to come in contact with the scientist, he reawakens Frankenstein’s monster, removed from its control by Ygor, and they battle. Once again, in trying to control his own fate and attempting to control nature, nature has fought back by bringing him face to face with another unnatural being. Frankenstein’s Monster, a being made up of the lives and bodies of multiple different people, comes as the perfect mirror to Talbot, another being that has come from attempting to play God with nature. It is only natural that the two seem to perish in the film’s cliff-hanger ending, where the town mob destroys the dam over the Frankenstein estate, flushing the two away.

Lon Chaney Jr is the only Universal Monsters actor to play his character in every appearance, portraying the character in all 5 movies Talbot appears in. The film’s depiction of the werewolf would become the blueprint for future appearances in film and television, and Universal would attempt twice-more to return the character to the big screen. A direct reboot would come in Joe Johnston’s The Wolfman in 2010, and then a different take on the material in Leigh Whannell’s Wolf Man in 2025.

Creature from the Black Lagoon

Years: 1954-1956

Featured Films: Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), Revenge of the Creature (1955), The Creature Walks Among Us (1956)

The final core franchise of the Universal Monsters, Creature from the Black Lagoon started as a franchise well-after all the other pop culture juggernauts of the Universal Monsters were already done and has finished meeting on-screen. The Creature Walks Among Us, 1956’s final movie of the three Creature from the Black Lagoon movies, is also seen commonly as the final film of the Universal Monsters. The initial 1954 film follows a group of scientists who encounter a merman when travelling to the Amazon, they attempt to capture this monster to study it, while the merman becomes interested in Kay, a female scientist in the group. This attempt to study the merman becomes its unifying theme with The Wolf-Man and the rest of the Universal Monsters. Though released years after the end of the films collaborating, the film’s exploration into the attempt to control and study nature unifies it. Though the sequels, 1955’s Revenge of the Creature and 1956’s The Creature Walks Among Us, faired less fairly with critics and essentially serve as redoes of the initial film’s plot, they further the scientific exploration into the merman. He is transferred to an aquarium and used as an attraction in Revenge, and then surgically experimented on until he can survive on land and blend into society in Walks Among Us, and these former versions position the creature as more of a victim than coldblooded monster. There are still sympathetic protagonists outside of the monster, but through the film’s underwater photography, a lot of the world is seen under the lens of the creature. This makes this franchise stand largely apart from many of the central Universal Monster franchises, the creature is opposed to the world of man, from our governments and power structure through its own unpredictable nature, and the films aligns themselves with so.

Unlike many of the other Universal Monster franchises, there has been no reboots of the Creature from the Black Lagoon series, no matter how many attempts there has been, with a current James Wan directed reboot announced this year.

Crossover Films

Years: 1944-1955

Featured Films: House of Frankenstein (1944), House of Dracula (1945), Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (1951), Abbott and Costello Meet Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1953), Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy (1955)

Sometimes referred to as ‘monster mashes’ Universal Pictures soon come to see the profitability of mixing their classic Universal Monsters together in filmic team-ups. After the success of Frankenstein meets the Wolf Man, Universal released the two-hit release of 1944’s House of Frankenstein and 1945’s House of Dracula. These two films followed up the cliff-hanger ending of Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, showing a rare connectivity between these films. In the days before regular cinematic universes, where audiences assume that all films must connect and align with each other’s continuity, this cinematic universe plays hard and loose with its timeline. This lack of narrative cohesion is even shown in these two films, with House of Frankenstein showing the death of Lawrence Talbot, only for him to be back alive and well in the following film. These films see the return of both The Wolf-Man and Frankenstein’s Monster, with the new addition of Dracula, here played by John Carradine. Dracula serves as essentially a side-storyline in the first House film, perishing in sunlight in the first act, as the action returns to the other two monsters. He serves larger narrative purpose in the sequel, where all three monsters request a gifted doctor to cure them of their ailments. Both films serve as an almost greatest-hits of each cinematic franchise, with Frankenstein’s Monster being ordered around by a scientist and wishing to be unmade, Lawrence Talbot wants to be cured from his werewolf side or die trying, and Dracula wishes to drink blood in scenes which recreate scenes almost identically from his first feature. Through the inclusion of new villains, the Mad Doctor and the Hunchback, the term monster mash becomes even more relevant here, ending this continuity with an all-out monster brawl.

This monster mash was then followed by 1948’s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, a film that mixes the world of the Universal Monsters and the comedy formed by the titled duo, becoming a horror-comedy, unique to this shared universe. Featuring the returning monsters of Frankenstein’s Monster, Dracula, The Wolf-Man and the Invisible Man in its closing minutes, the film follows Count Dracula, Bela Lugosi returning to the role, as he works to find a brain to reactivate Frankenstein’s Monster. In his search, he finds Costello’s character, Wilbur Grey, as the best fit for this brain surgery. Continuity continues to be confusing for this series, as the film once again disregards the ending of the previous film, with Talbot once again the Wolfman after he was cured in the previous film. The movie’s mix of comedy and horror works wonders to pair the styles of both the performers and franchises, the screwball comedy nature calling back to some of the strangest genre moments of the Invisible Man franchise. The movie ends with the three main monsters perishing, ending their stories here, in a riveting crossover film which marries their world to the worlds of fantastical comedy. Abbott and Costello would continue to crossover with horror legends in subsequent films, following with a science-fiction mystery in 1951’s Abbott and Costello Meet The Invisible Man. They would then crossover with a new Universal Monster, in 1953’s Abbott and Costello Meet Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and then conclude this universe’s crossovers with 1955’s Abbott and Costello Meet The Mummy.

Leave a comment